Guadeloupe: a French island somewhere between paradise and desperation

Author: Pierre Scordia

An uneasy feeling

Arriving at Point-à-Pitre airport, Pôle Caraïbe, we are somewhat surprised, even slightly disturbed by the signs indicating which queue to join: the European Union one is for Guadeloupians, Martinicans, Guyanese and all other European nationals whilst the other is for the rest of the world including the neighbouring islands of the Small Antilles. One suspects that there is some kind of anomaly or anachronism.

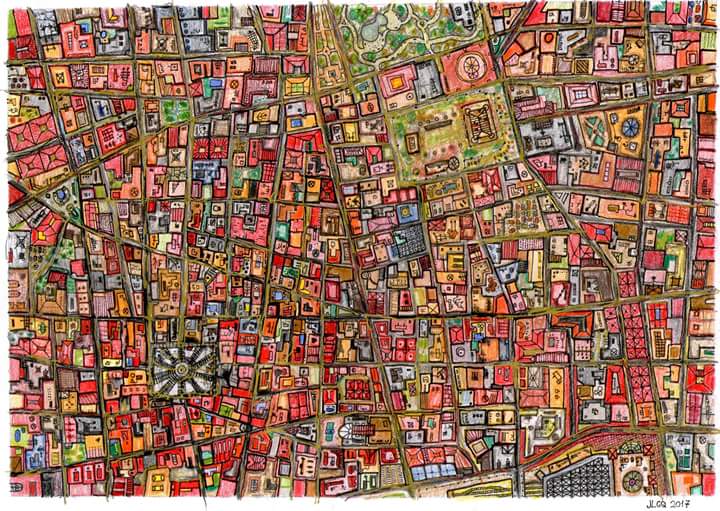

As soon as you leave the airport, you might be excused for thinking you are in metropolitan France: the cars have French number plates, the European flag above the F. The architecture of the terminal and other buildings are typically Gallic, as if all materials had been directly imported from France. The traffic signs on the roads are identical and it is surprising to have the use of a network of free highways on such a small island. Only the coconut trees, beaches and sugarcane fields remind travellers that they are indeed 6731 km from Paris.

If you take the time to scratch below the surface of this Caribbean postcard, you come to realise that the Butterfly Island is far from this seemingly rosy picture, the whole socio-economic system being in fact under perfusion, with 40% of the active population composed of civil servants of which the senior managers come mostly from France. The latter benefit from bonuses and other advantages to compensate both for their absence from the motherland and the island's high cost of living; native civil servants also benefit from salary perks and bonuses. However some of the native islanders denounce the presence of French bureaucrats, which contributes to inflation, increasing the cost of living.

It should be noted that the Guadeloupe Region operates on exactly the same territory as the Guadeloupe Department ever since the prosperous islands of Saint-Martin and Saint-Barthélemy became autonomous and thus detached from the Guadeloupe region. So why maintain two parallel administrations? A good question... Could it be to maintain job security and ensure the leaders of the French Republic get re-elected? The Guadeloupians rejected a new single assembly by more than 60% in a 2003 referendum, preferring to preserve the status quo and rule out further reforms. Since then, the aberration of a double administration has been preserved. Let us not forget that the election of former President François Hollande in 2012 benefited in no small part from overseas French territories, Guadeloupe having supported the Socialist candidate with 72% of the vote. President Macron and his new party would come up against great opposition here if they plan to trim expenditures; only 1 out of 4 MPs in Guadeloupe belong to la République en Marche.

Another 40% of this small friendly nation are unemployed but enjoy a considerable number of welfare benefits that made Guadeloupe the envy of Mayotte (the secessionist Indian Ocean island of Comoros with the highest birth rate in France) which wanted to become as “rich” as Guadeloupe. In 2011, it finally obtained the same French departmental status as Guadeloupe. In these former colonies, even if a certain lack of love for France is palpable, people are nevertheless dependent upon the French welfare state. People even refer to "zipper benefits” for girls getting themselves pregnant, a practical way to become eligible for council housing.

A dramatic reality

There is a dramatic reality behind all this: the Guadeloupians emigrate more and more to the metropolis: to France, Canada, the United States, England and the United Arab Emirates in search of employment. For example, in the centre of the beautiful little town of Le Moule, in Grande-Terre, many beautiful wooden houses have been left abandoned because their inhabitants have moved away to settle in France and elsewhere. On the other hand, French metropolitans are increasingly arriving to invest in real estate and tourism, an influx of such magnitude that the writer Martiniquais Patrick Chamoiseau sees in this phenomenon a “genocide by substitution": France thus imports cheap labour while exporting its civil servants and pensioners. Some Antilleans fear that the island’s Negritude is threatened, despite the fact that more and more Haitians and Dominican Republic nationals, in search of prosperity and security, are illegally taking up residence in the French West Indies.

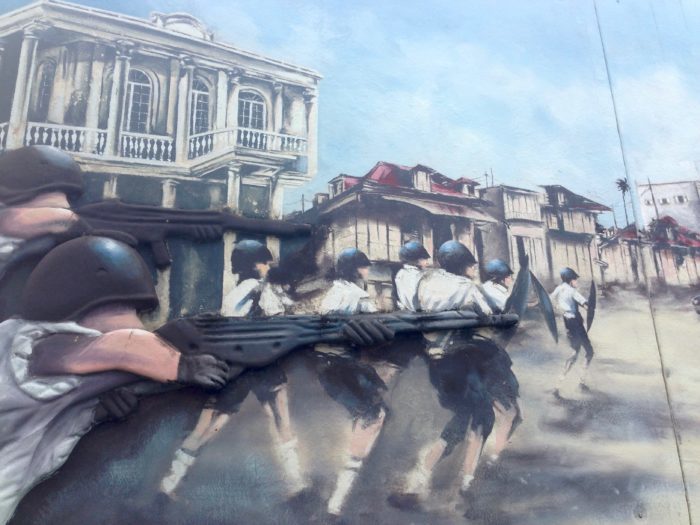

If we take the time to listen to Guadeloupians, we come to realize that as a nation they feel despised by the French. The wounds in their collective memory are profound: slavery, all hopes of the French Revolution dashed - Guadeloupians were freed in 1794 but re-enslaved in 1805 on Napoleon’s orders (the Emperor was married to the plantation owner Joséphine de Beauharnais, a Martinican Creole "béké ", meaning of European descent). There are the thousands of Indian families who came to work in sugar cane fields after the definitive abolition of slavery in 1848 who even now barely mix with the rest of the population. Let’s not forget the conscription under the Third Republic of young men to be used as cannon fodder, the bloody repression by police during the strikes at Pointe-à-Pitre in 1967 resulting in a toll of 100 deaths, and last but not least the "chlordecone" scandal, a pesticide banned in France and throughout the European Union but which was given an administrative exemption for banana growing in the French West Indies, under the pressure of the rich Martinique békés, owners of large plantations, resulting in such pollution of Guadeloupe’s groundwater, as well as its rivers and coastline that the crayfish are unfit for consumption - Le Monde speaks of a real ecological disaster.

Astonishingly, Creole, very much a living language, still has no official status. Some Guadeloupians, not having had a full education in French, feel daunted by the complexity of the long administrative forms drawn up in Parisian offices and this may well serve to reinforce the impression that they are still colonized or acculturated. Moreover, there are no subtitles in the News for those who do not understand French very well; it really seems that the Republic prefers to turn a blind eye in the name of the sacrosanct “one nation one state”, whilst maintaining that the EU promotes diversity and accessibility for all!

"But you still have such beautiful houses and excellent roads thanks to all these French subsidies!” I had the impudence to declare one day. Obviously, this is the sort of scathing and paternalistic little phrase that enrages Guadeloupians. These subsidies in fact serve to keep the island in a state of dependence and passivity. Unlike Dominica and Saint Lucia, which are much poorer, Guadeloupe does little to adapt to the economic climate or its tropical environment. Market gardening is not encouraged and construction is not adapted to withstand cyclones. After all, Paris is there to pay for the broken pots and Guadeloupe does not have the right to self-determination. The economy is for the most part turned away from the Caribbean and America; being a European Union territory, it is far simpler to import products from France than neighbouring islands. Even with regard to tourism, it was not until 2016 that Norwegian, the low-cost Scandinavian airline (registered in Ireland), set up low cost direct flights connecting Point-à-Pitre to New York, Baltimore and Boston, breaking up the quasi-monopoly of Air France and Air Caraïbes (the latter a French family business owned by the Dubrueil family). These new flight connections will make the United States more popular than Paris as a vacation spot and in the long run could Americanise the entire population of the French West Indies since they benefit from a US visa waiver.

A Booming Art Scene

As for the art scene, the situation is delicate. An artist who wishes to be professional is up against an obstacle course, because on this island, popular art and culture are going strong! For example, the artistic association L'Artocarpe - having enjoyed international success in the city of Le Moule by creating numerous residences in a three-storey house owned by its founder, the artist Joëlle Ferly had to comply with European standards on disabled access. But how could Ferly finance the construction of an elevator in her house? She had no choice but to stop all her public-oriented activities and relocate to New York, until she finds a solution.

There is also the dynamic Thierry Alet, an artist who has worked on the collective memory of the West Indies with his famous sculpture "Blood", a work commissioned by the Clément Foundation, in other words financed by the great Béké magnate of Martinique, Bernard Hayot (a man in control of large-scale distribution, car dealerships, agri-foodstuffs and a share of imports into the French West Indies). This masterpiece has even been the subject of an article in the prestigious New York Times. In fact Alet, living between the West Indies and New York, has opened two galleries in Basse-Terre and Jarry, the Point-à-Pitre industrial and commercial zone, giving new breath to the cultural life of Guadeloupe. After "Blood", Alet produced another interesting work entitled “la voleuse d’enfants” (“The Child Thief”) - a work made up of small pieces of wood painted in different colours. It can be viewed in the impressive Memorial ACTe, in Point-à-Pitre.

The architecture of this superb museum dedicated to slavery and the history of Afro-American peoples is uncannily similar to the Museum of the Mediterranean in Marseille. But we are assured that the firm of architects who built it is fully Guadeloupian! This pharaonic museum with an uninterrupted view of the mountainous island of Basse-Terre cost a staggering 83 million Euros, a colossal fortune for a country in the midst of a full economic slump. The most surprising thing is that this site was built in a dodgy neighbourhood in the depraved and dangerous Point-à-Pitre. To get there, you must pluck up the courage to cross a neighbourhood filled with Dominican prostitutes and drug traffickers.

It is estimated that it would take at least 1,500 visitors a day for the ACTe Memorial to become profitable, yet when I was there in April 2016, I was the only tourist in the huge lobby where four receptionists welcomed me with a big smiles. Some Guadeloupian journalists predicted that there would be an average of 150 daily visits... For the inauguration of this spectacular museum on May 10th, 2015, the Region of Guadeloupe took great care to conceal all these depressing realities from François Hollande and the other invited heads of state from Africa and the Americas.

ACTe Memorial

ACTe Memorial

An outpost of the failure of the French Republic?

But let's look on the bright side: the struggles and successes of the above mentioned artistic entrepreneurs trained in North America and Britain give reason for hope (Ferly lived 15 years in London, Alet is still based in New York). More and more French Caribbean people think that a viable prosperity for Guadeloupe could come about with a better integration of the island with the rest of the Caribbean world within a North American context. A decentralisation or even a withdrawal of the French state would undoubtedly be desirable in the long term in order to emancipate citizens by allowing them to fully engage. Otherwise Guadeloupe could go the way of the many outposts of the French Republic that risk going bust. France can best achieve financial security through supporting private entrepreneurship and undertaking an in-depth reform of its overseas departments, communities, regions and territories.

During the 45 day strike in 2009 against the high cost of living that has paralysed the island, protestors demanded a greater autonomy for Guadeloupe. This event was perceived by many Guadeloupians as a sign of hope because they found that they could be economically self-sufficient without a reliance on goods and products imported from France. It remains to be hoped that common sense will prevail in Paris and Basse-Terre (the capital of the department of Guadeloupe) and that a significant degree of autonomy will be granted to this Caribbean island without undue interference from the French administration. But, as a long-term French resident of the island confided in me, it is more than likely that the Guadeloupians will reject any change to the status quo, as they did in the 2003 referendum, unlike in Martinique. Guadeloupians would certainly wish for independence or autonomy in theory, but many are afraid of the unknown. "We are no longer in the nineteenth century. Paris is no longer the real problem and I even believe that France would be ready to cede a large autonomy to the island as it did, notwithstanding many hiccups along the way, in New Caledonia and Polynesia. It seems however that there are very powerful lobbies in the French West Indies that would obstruct change in Guadeloupe in order to preserve selfish economic interests. This unfortunately strains the financial resources of the “Papillon Island” and those of the indebted French state. Real reforms from President Macron urgently need to be put in place giving full political and fiscal devolution to the overseas territories.”

I left Guadeloupe with a sense of hope that Guadeloupians will begin to take responsibility for their destiny and that this process might be accelerated by the new government in France; Emmanuel Macron and Édouard Philippe declare themselves Girondin, men who (not only for overseas but also for French regions) favour a light form of devolution.

FΩRMIdea London, August 18th 2017. En español | En français

Published in a two part series in The Voice (UK)

Photo credit: Pierre Scordia

Photo credit: Pierre Scordia

I couldn’t resist commenting. Well written!

My grandmother was born to an African prostitute in the late 1800s. The upstairs brothel was about 5 doors up the street from the entrance to the port. Grandma was put in service to a French family when she was about 5, where she remained until she migrated to the US about 1905 as an indentured servant.