The Restoration of Napoleon

A sixty year cinematic detective story

By Maurice Caldera

I can’t quite recall when my interest in silent cinema began, but I do remember as a child tuning in every week to watch Kevin Brownlow and David Gill’s 13 part TV documentary, Hollywood, about the birth of the motion picture industry. I can still remember that it was on a Monday night at nine o’clock, and as far as I was concerned it was the only show in town. As I watched those impossibly distant black and white fragments from another time and another world, accompanied by Carl’s Davis’ achingly nostalgic score and James Mason’s smooth as silk narration, I wondered under what circumstances would I ever see these films again.

Fast-forward a generation and a half, and those same films, along with countless more, not to mention the entire Brownlow series itself is available on YouTube. On seeing them again over the years, it is the sheer scale of some of those films which struck me all over again, Cecil B De Mille’s or D W Griffith’s gargantuan sets, ancient Egypt recreated, complete with untold extras crowding into the frame, doing the job that CGI would be doing one hundred years later to arguably lesser effect. More and more films or fragments are discovered all the time, but the mind boggles at how many treasures we have lost along the way.

For decades, silent film was forgotten, and derided, even by some of the filmmakers themselves. The films were chopped up and the footage used for laughs to the rink-a dink-dink of piano accompaniment, self-congratulatory proof of how far we had evolved in our execution of this most celebrated of art forms. It is filmmaker, producer and cinema historian Kevin Brownlow, more than any other person, who has championed silent filmmaking, expanding our understanding of what great cinema means, putting the silent screen’s great works alongside their long feted talking counterparts. It is also Brownlow who we have to thank for the film event of the year, or decade, or perhaps of all time, the restoration and re-release of Abel Gance’s staggering 1927 five and a half hour masterpiece, Napoleon, or to give it its full original title, Napoleon vu par Abel Gance.

“It was 1953 and I was still at school,” says Brownlow. “I’d borrowed a silent French film by Jean Epstein from the library and it was awful. So I rang the library and asked if they had anything else. They said they had Napoleon and the French Revolution.” The prospect of this unknown historical film did little to enthuse Brownlow, but that was the only thing they had. As he waited for the film to arrive, he contacted the British Film Institute and enquired as to what it might be. Although they couldn’t be sure, they suggested that it might be a 1927 film by French director Abel Gance.

“When the film arrived, we played it on the wall and I’d never seen anything like it. This, I thought, is what cinema should be.” Anyone who has watched this unique work of cinematic spectacle will understand what that experience must have been like, they will also understand that the film defies categorization, it is quite simply in a league of its own. It is this same greatness and innovation that sealed its fate over the years. It was too long a film to screen, too complex technically, and so it fell into obscurity. But for Brownlow, the sight of those two reels projected on the wall of his family home was the beginning of a long, rewarding and at times frustrating adventure that has brought us this restored version.

You’d be forgiven for thinking that film restoration involves handing over celluloid reels to labs and waiting for them to put them together again, but at a recent talk at the National Film Theatre in London, what Brownlow describes as restoration sounds a lot like cinematic detective work. In the first instance, no actual full print survived, the prints that were available were in poorly preserved fragments, the distributors often cut their own version for the screen, (MGM released a 75min version in the US) and so this film like so many others, was bastardised and diluted again and again until what remained bore little resemblance to anything at all vu par Abel Gance.

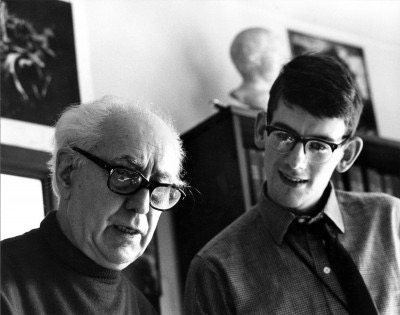

Brownlow put adverts in Exchange and Mart, contacted the Cinémathèque française and rifled through junk shops and flea markets in London and Paris and beyond, in search of more reels. Bit by bit the reassembly began to take shape. He wrote to Abel Gance who was then in his sixties, met him soon after, and a lasting friendship formed between the two. “He was so friendly, so surprised with this little kid who was besotted with his work," recalls Brownlow. It was in 1968 that this little kid, now an adult decided to embark on a full restoration.

Gance himself was born in Paris in 1889, and like so many of the early film people came into the movies as an actor. He quickly felt he could do a better job than the directors, and eventually he was given the opportunity to do just that. From the outset he was pushing the boundaries of the form, but always with an interest in telling psychological stories, in other words getting inside the character’s heads. In 1919 he made the anti-war film J’Accuse which put him on the map, but it is his 1922 film La Roue, (which is reported to have a running time of nine hours), in which many of his cinematic flair was on full display. This included his rapid cutting techniques, a good few years before Eisenstein and his generation of Russian filmmakers were experimenting with their own rapid cutting. The Russians were open about the debt they owed Gance, though curiously it is they who are credited with inventing this style of fast cutting known as Russian montage. Gance took a lot of the inspiration for his formal experiments from the French avant-garde, yet the form never distanced the audience from the narrative and characters, on the contrary they were made more vivid through the experience of cinema. He went on to make films well into the sound period, but never to reach those same heights again.

By 1927, Gance was well established enough and thought enough of his own merits to include his own name in the title, to be uttered in the same breath as the great man himself, Napoleon. The studio gave him money for six films, and the all-or-nothing director threw all the money on one, Napoleon vu par Abel Gance.I had only ever read about this film, and seen a few clips and stills, and as I made my way to the National Film Theatre in London one November afternoon almost ninety years after the film was made my mind was stuck in much more prosaic territory…all I could think about was the running time, and how I would get through it. Yet, as the lights dimmed and I settled in, I, like Brownlow, and so many other people since, am quite simply blown away.

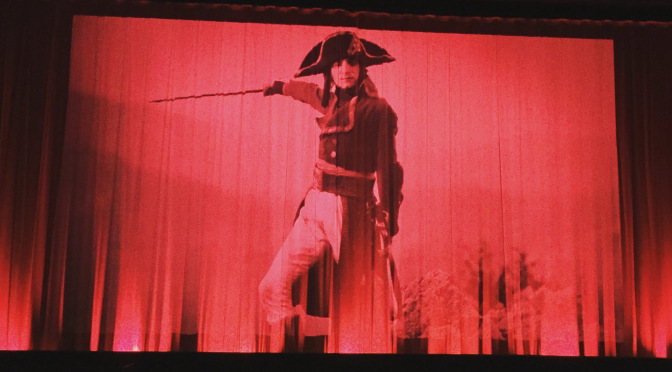

The film, which covers a relatively brief period in the life of Napoleon, from a child to the moment where he takes command of the exhausted Italian armies, is relentlessly inventive. It uses the camera in ways that I have not seen before, for that period or any other period. The editing is wildly creative, crashing images together, in breathless succession, superimposing, splitting the screen. He places the camera in the midst of the action, hand-held, decades before anyone ever knew what that was which often lends it a documentary feel. Different segments are tinted in different colours, and so it goes on. A scene of Napoleon in a storm at sea is juxtaposed with a scene at the Paris Convention in full climactic debate, and it is shot in the same way, as though the camera were on the high seas, swinging furiously as it observes the revolution imploding towards the Reign of Terror. The battle scenes are brutal and vivid, and once again the camera is in the thick of it, creating such authenticity in that chaos that you can only marvel that it was ever managed at all. Indeed the entire film has an authenticity to it that seems at odds with this heightened visual language. The overall effect is that you are dazzled into this world, so that you have the feeling that you are witnessing these events first-hand, something, conversely that can only be achieved through this visual language, the illusion would have collapsed under the weight of the spoken word.

And then it comes. The famous triptych. You know about it, because you’ve read about it, because all commentators of the film make mention of it, how could they not? You might have seen an image or two, but I had seen nothing of it. And when it comes, it is like nothing you have ever seen or will ever see again. As the story rages on, the screen opens up, discreetly alerting the audience to its imminence. From one screen, we go to three. Nothing prepares you for this visual feast, and I will not spoil the surprise, but if you have been paying any attention at all, you will have understood that Gance would not let a good triptych go to waste without exploiting it visually to its limits and beyond. It is a cinematic experience like none other.

Once again it was Carl Davis who was asked to compose the score, (indeed it was also Carl Davis who financed the restoration), except he was only given three months to do it. “The original score by Arthur Honegger was lost so I thought it would be very interesting to make it like a counter performance, a portrait of the music of Napoleon’s time, using the work of Mozart, Beethoven and Haydn. We acted like tailors. We amplified, perverted and did all sorts of things to the music.” A score had been composed by Carmine Coppola for his son’s (Francis Ford) revival of an earlier cut in 1981, but Davis succeeded in creating or recreating a score that seems so organic to the operatic nature of the film and the events, that it's now difficult to imagine anything else.

Like those Hollywood epics of the silent era, what is staggering about Napoleon is the sheer volume of people in it, actors and extras and crowds and more crowds. Those scenes at the Paris Convention have them hanging from the rafters, literally. In every scene you are struck by the stories that are taking place at the edges of the frame, like the work by a great master. In Brownlow’s chapter on Gance in his book on silent cinema, The Parade’s Gone By, he says, “in Napoleon not one extra of the thousands that pour across the screen betrays the fact that he is acting a part. Gance achieved the ultimate in reconstruction, he recreated the period not merely through costumes and sets but through a metamorphosis of those taking part. While they were shooting, they were hypnotized into the eighteenth century.” The effect is that the narrative is not confined to the foreground, what we witness, are layers and layers of stories, played out by extras in full surrender to the period and their role in it. It is one more sign of a truly great director.

The adult Napoleon was played with an impenetrable intensity by Albert Dieudonné. So profoundly was Dieudonné affected by this role that he vowed never again to act unless it was in the part of Napoleon. True to his word, he did make a few more films but always only as Bonaparte, and in fact went on to become an authority on the great man himself. When he accompanied Gance on one of the screenings held here throughout the years in London, he refused to travel to or from Waterloo station, and would not go anywhere near Trafalgar Square.

Gance was so ahead of his time that he even made a sort of making of whilst he shot Napoleon, decades before they were ever dreamed up, as though he too had one eye on its posterity. One can imagine Brownlow’s reaction when he first heard of its existence, and when he first glimpsed it. At his recent talk in London, he screened some footage from this making of, and it is here that we can glimpse these innovations at work. In the opening scenes of the child Napoleon leading his school chums into a snowball battle foreshadowing the battle scenes to come, we can observe a range of makeshift contraptions that he has devised for the camera, some difficult to categorise, others prototypes of what are now industry standards, such as a camera strapped to an operator, like an embryonic steadicam, almost fifty years before Kubrick made use of it in The Shining.

As Brownlow says, “in an age when people will happily watch Lawrence of Arabia on their mobile phone, I’m proud to be bringing Napoleon to the cinema. Napoleon is pure cinema and cinema was designed for sharing. There’s something about the way it was shot that makes it like no other. I can’t tell you how many people, having seen our restoration have said ‘that was the greatest experience I have ever had in a motion picture theatre.” I count myself as one of those people who have fallen under its spell. As I leave the cinema and walk along the Southbank on this autumn evening having sat through six hours of this unique experience, all I can think about is doing it all over again. The film is indeed like no other, and it has to be seen to be believed.Napoleon is on general release in the UK, on DVD and Blu-ray.

FΩRMIdea London, 22nd November 2016.Maurice Caldera is a screenwriter, author and visiting tutor at the National Film and Television School.

Wow! Excellent Post. I really found this so much informative. It is what I was looking for. I would like to suggest that you keep sharing Such type of information please. Thank you so much.