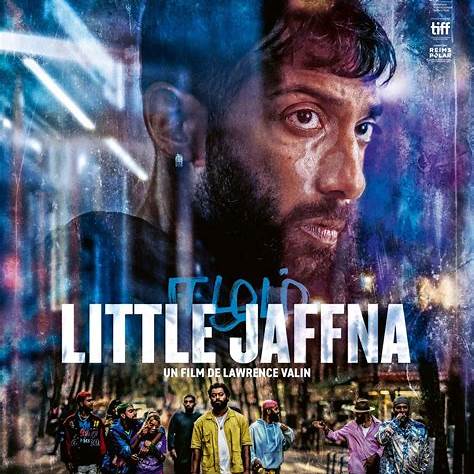

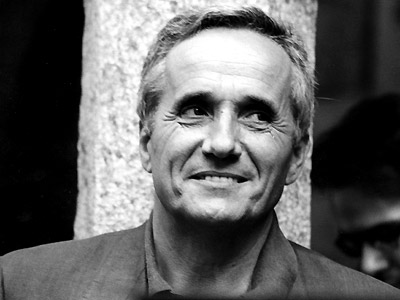

Marco Bellocchio

by Beverly Andrews

Film directors’ careers tend to follow a similar trajectory; first they achieve international recognition with their accomplished first features and then they go on to cement their professional reputations with each successive film. Once they reach the pinnacle of success, their work gradually falls out of favour to be replaced by that of younger directors. Some then can even find their work forgotten. The acclaimed Italian film director Marco Bellocchio's career has followed a very different and far more unusual path. Although like many renowned filmmakers his first feature received global recognition, from that point on his career has charted its own unique course. This summer, London's British Film Institute has mounted one of the largest retrospectives of Bellocchio's work ever to be shown outside of Italy giving British audiences an all too rare opportunity to see the work of one of cinema's greatest directors.

Unlike many of Italy's cinema giants such as Bertolucci or Antonioni, who came of age in the sixties and whose work was very much driven by political events, or more contemporary social commentators such as Nanni Moretti, Marco Bellocchio's work is both deeply personal as well as being that of a social commentator, documenting the many social and political changes which have taken place in Italy over the years. There are few film directors whose canon of work is as diverse as Bellocchio’s and few whose work so late in their careers is as urgent and vital as ever.

Marco Bellocchio has spent much of his fifty year career questioning established ideologies as well as struggling with moral questions, while at the same time demonstrating a willingness to see the other side. This element of his work was very much on display in his very first feature Fists in the Pocket. A film which Bellocchio states is very much “a portrait of my adolescence”. With almost no money of his own, it was only through the generous support of his parents that he was able to make this film. This fact is somewhat ironic given Fists in the Pocket is a savage attack on the institution of the family! Despite that fact, the film went on to international success and its recognition announced Bellocchio's arrival on the world stage.

But early success for a young director can be a dangerous thing and Bellocchio has said in interviews that looking back now in retrospect he can see that like many young directors who won acclaim at the beginning of their careers he found doors opened up for him but didn't always feel ready for the opportunities which were given to him. He was also, like many other film directors of his generation, deeply affected by the political upheavals of the times and this in turn affected the films he made. China is Near, a follow-up to Fists in the Pocket, is a political satire about the life of a university professor who is chosen to be a socialist candidate. Although an accomplished work it did not achieve the same international recognition as Fists in the Pocket and to some extent was seen at the time as a failure. Meanwhile, he watched the star of his friend Bernardo Bertolucci rise. Eventually his career went global with such international successes as Last Tango in Paris and a few years later The Last Emperor.

While it was still a struggle for Bellocchio's work to connect to international audiences, Bellocchio says of his career that once he became involved in the political upheavals of the late sixties, he pushed cinema away and moved toward more politically engaged work. In an interview promoting the season Bellocchio says, referring to his friend Bertolucci, “I was young, so there was a tiny bit of jealousy and envy, especially for the freedom that such an international success can afford a director.” “But,” he concludes, “that was a very long time ago.” Bellocchio also had to contend with the suicide of his twin brother in 1968, something which deeply affected him, along with the sense that the socialist utopia he and many of his generation had been fighting for was perhaps doomed to failure. The films In The Name of the Father and Victory March perhaps best reflect this political pessimism. These events triggered a period of introspection and a fascination with psychotherapy. He sought and found help from Dr Massimo Fagioli, who went on to become both a friend and a collaborator. Bellocchio speaks of this period as a kind of rebirth.

In the years that followed their professional collaboration it does appear as if Marco Bellocchio did indeed experience a kind of career rebirth since his work suddenly had an even greater power and contemporary resonance. Two films stand out during this period, firstly the extraordinary Good Morning, Night - a look at the events surrounding the kidnapping of Italy's former Prime Minister Aldo Moro. The film presents these events from the perspective of one of the kidnappers, a woman who goes on an internal journey of forgiveness for the now frail, old and sad figure of Aldo Moro. She grows to see him no longer as the architect of a repressive state but possibly as another one of its victims. Bellocchio states about this particular film that although on the surface it is a political thriller, underneath it is also very much about his relationship with his father, where years of therapy propelled him on his own personal journey of forgiveness.

Secondly, Bellocchio went on to make an even more extraordinary film in 2009, the still topical Vincere, an account of the little known story of Italy's fascist leader Benito Mussolini's first wife, Ida Dalse. Dalse gave up everything she had to support the then struggling Mussolini, and it was only through her financial support that he was able to start his fascist newspaper, II Popolo d'Italia, a cornerstone of the Italian fascist movement. They had a son together before Mussolini abandoned her in order to marry another woman. He subsequently denied ever having known Dalse and their son. All records of their marriage were destroyed (although there is a record in Milan of Dalse receiving a government pension during the war, a pension which would have only been given to wives of serving soldiers). Dalse was eventually forced into an insane asylum where she died several years later. Her son was also forcibly incarcerated in an asylum where he too died. His death is now attributed to the coma-inducing medication he was given there. Dalse's story is one which is incredibly important to tell today since Italy's fascist right (as well as right wing parties throughout Europe) are seeking to rehabilitate Mussolini's reputation and show him to be a loyal, loving husband and father. Vincere paints a dramatically different portrait, a portrait of a man driven by ambition, someone who was prepared to sacrifice all those close to him, anyone in fact who might have stood in his way. It is an important story to tell and Bellocchio does so with a combination of flair and a deep compassion for the title character of Dalse. He also helps in the process to illustrate the fact that populist political figures rarely have the good of the people they represent as their driving motive.

Bellucchio says of his most recent work that there is a greater desire now to look out into society. To no longer destroy but rather seek to understand. This BFI season of his work shows a film maker who after a fifty year career is continuing to make provocative, original work and is very much a director at the height of his powers.

FORMIdea London, 18th August 2018. Lire cet article en français

Fists in the Pocket

Fists in the Pocket China is Near

China is Near Vincere

Vincere Vincere

Vincere