Land

Rewati Shahani was born and brought up in Mumbai in a family directly affected by Partition. The topics of migration and place have been constant themes in her work.

In 2018, she returned to Mumbai for her first solo show in India, Tides, a study of geography and migration. LAND is a continuation of this study.

1. You recently had an exhibition in London called “LAND”. Could you tell us more about it?

Rewati Shahani: LAND was my first solo show in London, and was a study of contemporary notions around place and migration, and how these are made manifest by countries’ borders. It was set against the backdrop of the division of lands by European powers during the 20th century: I wanted to explore how this carving up of places and peoples, done by drawing new lines on old maps, continues to shape the way we understand nationality, and belonging, today.

2. Where does this fascination about borders come from?

Being from India, with roots in what is now Pakistan, and living in London, my personal interest in what it means to live in one place but be ‘from’ another runs deep.

I’ve drawn on the themes of place and migration throughout my career as an artist. Both are inextricably linked to borders, as these set the parameters of a country’s understanding of its own identity, and what represents the ‘other’.

A lot of the identities that were created along with the nation states at the end of the colonial era still persist today, but sit uncomfortably with more modern trends of human migration.

These deep-seated notions are tied closely (and at their inception, deliberately) to race and religion, and so craft our popular understanding of what it means to be Pakistani, or Nigerian, or British. But these often refuse to bend, or are willingly blocked from doing so, to recognise the multi-layered existences lived by people like myself and my family. This is why so many people of colour who live in or were born in the West are often asked where they are really from.

This balancing act, between identities, migration and belonging, is only going to become more delicate, as climate change, in particular, prompts ever greater numbers of people to leave their homes in search of more stable conditions.

While much of the focus on the migrant ‘crisis’ Europe has experienced since 2015 has been on Syrian refugees, a significant number of those that make the perilous boat rides to European shores also hail from some of the countries worst affected by climate change, such as those in the sub-Saharan region of Africa.

Climate change is a man-made problem, and is forcing people from their homes – even as borders, also man-made, are fortified to force them to stay put. This problem is not going away.

3. What were the consequences of the partition for your family?

I was born in Mumbai, but my parents are Sindhi [Sindh is a region of what is now Pakistan]. In 1948, the year after Partition, my father became a refugee, coming to Mumbai. He was completely uprooted, travelling with his entire family on a crowded train for a journey of several days, leaving almost all of their possessions behind.

He remembers the women of the family raising their hands, palms outward – a gesture of rejection, as if pushing something away – as they crossed the border. A border less than a year old, and that created, overnight, two countries where once there was just one, his.

He still remembers his childhood home fondly, though has never been back to see it, and I grew up listening to stories about his time there.

It always seemed so unjust that that whole side of my family should be cut off from their roots – and therefore, my roots – due to lines drawn on maps. The topic has become something of a focus for my family; my father is a film-maker and has studied Partition frequently in his work, and my sister recently completed a PhD on the topic.

4. What countries have you chosen? Why those countries?

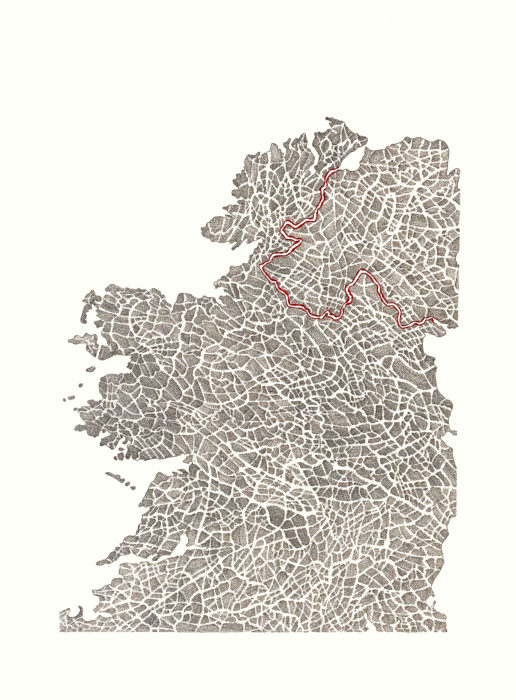

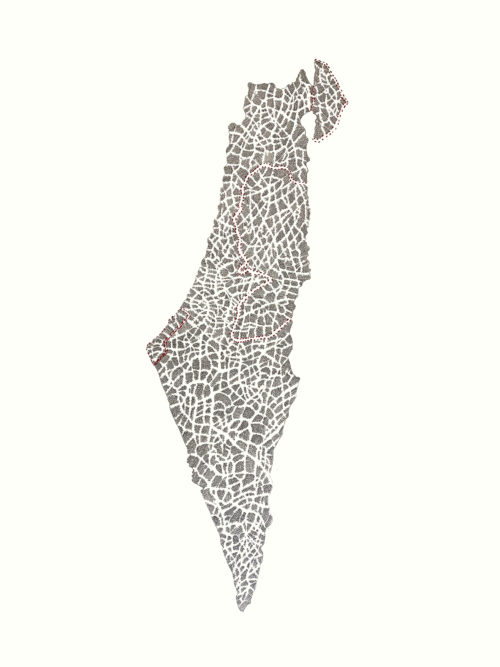

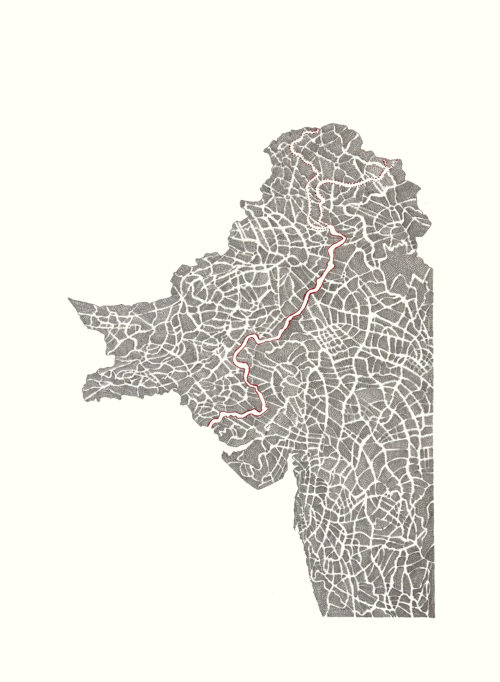

The maps shown in LAND reproduce the borders of India with Pakistan and Bangladesh (originally created as ‘East Pakistan’), Ireland with Northern Ireland, Israel and Palestine, and Syria with Iraq.

All of these borders were created throughout the 20th century, almost exclusively by British administrators, and typically along ethnic or religious lines. The effects of the Partition of India are well known, and of course most personal to me. Ireland, too, was also split up along religious lines.

The drawing of Israel’s borders – still ongoing and the root of much political tension in the region – has been arguably the most continually divisive, while the rampaging of ISIS in 2016 specifically targeted the border separating Iraq and Syria as an ideological affront to their own nefarious attempts at nation-building.

But I want it to be positive, too. The intricate detailing that fills the land both sides of the red border lines show that in spite of politics, war and unrest, ultimately they are home to countless lives, cultures and people; the borders come and go, but these shared histories remain.

Some of the earliest Hindu civilisations were formed in current-day Pakistan; India is home to some 190 million Muslims. In the UK, the prevalence of Irish pubs and surnames (my husband has an Irish surname, though was born and bred in London) speaks of the exchange of peoples around these islands, too. I want to recast popular binary understandings of nationhood.

5. What is your technique for drawing those maps?

It’s complicated. First I source accurate maps, I follow the key details and scale it up by hand, using either sections of the map or whole forms to make new shapes. Only then do I move from pencil to pen. The rest is a relentless, close-in focus on the details; I often draw for hours at a time, and late into the night.

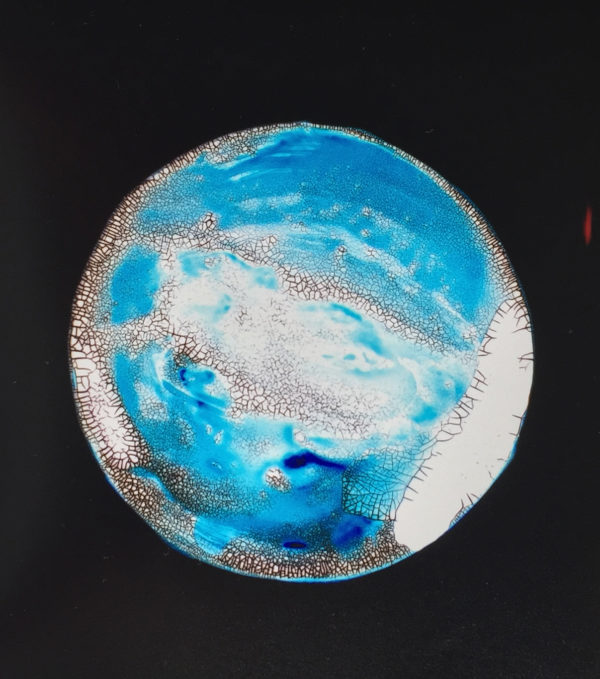

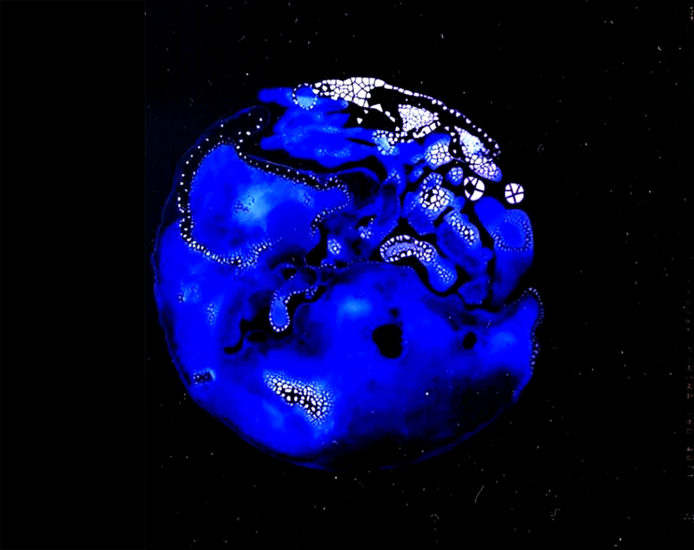

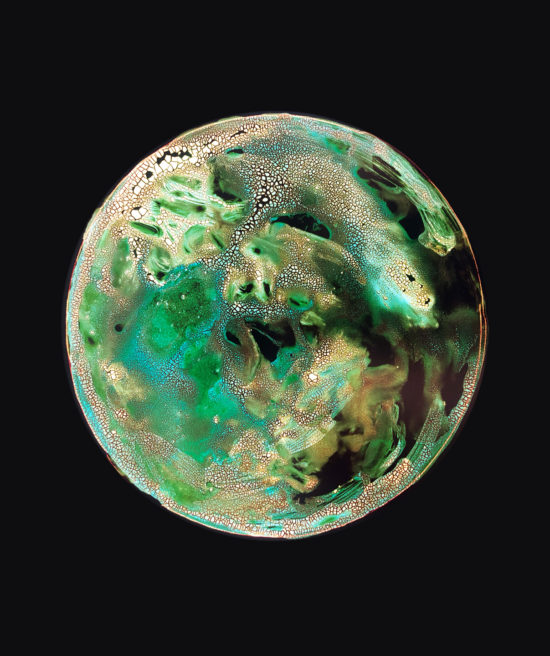

6. In your exhibition, we noticed many circles that could be planets and moons as viewed from space. Could you tell us more about them? What do they represent?

The circles can be seen as planets, or moons, and their geological aesthetic is designed with this in mind. But they are also an allegory for the fluidity with which the world’s people move, exist.

Circles have long been a symbol used to represent the ‘whole’; from early Buddhist mandalas to the ancient Greeks’ appreciation of its perfect geometry. I wanted to use this to represent the nation state, which relies on the geometry of physical borders to define its ideological ‘whole’, and to break each in a way that is not destructive but beautiful.

You will see that none of the circles are continuous, each has had its exterior line broken and recast in some way, such as with diluted ink swirling inwards. I try to represent the flows of people that join our ‘whole’. Though often challenging ideologies, this movement of people helps shape where – and how – we live. The mark making was a physical response to all that’s happening in the world politically and environmentally.

7. We were so impressed by their beauty that Form-idea bought one of them. How do you get this amazing blue shade?

The photographic works in the show aren’t in essence ‘photographs’. That is, no camera is used; instead I draw directly onto the negative, then once the ink has dried, have them hand-printed.

As such, everything in the process needs to be done ‘in reverse’, so to get the vivid blue when printed, I use a mixed murky orange ink. It often takes several attempts, as the drying process is delicate – the negative is a semi porous surface, the pigment of the ink sits on top as it dries and the water evaporates, this forms the crazing (crackled effect) which lends itself to the idea of the land being carved, farmed, formed and, of course, of borders themselves.

This has a similar effect as with the detailed method of the map drawing. It takes hours, even days, to dry. This is what allows the miniscule craters and cracks to form, but also drives my photographic printer – John McCarthy, at Labyrinth on Roman Road (in the same building as LAND was held) – mad.

I work with very closely with John throughout the process and to get the right balance of colour saturation and the crazing. He’s a magician with colour printing and pushes me to always experiment a bit more. This requires plenty of patience (on his part)!

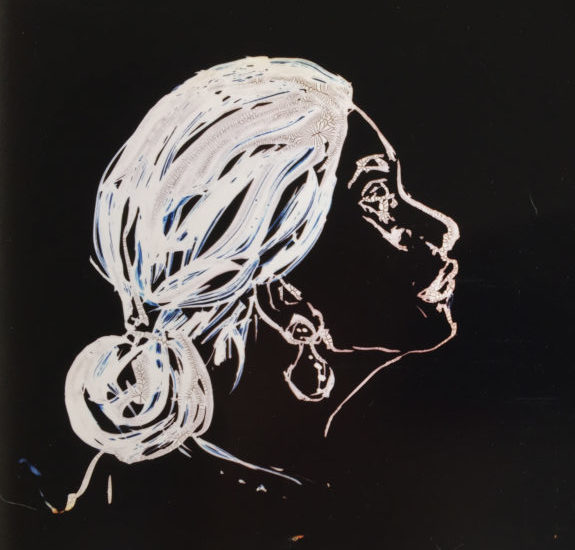

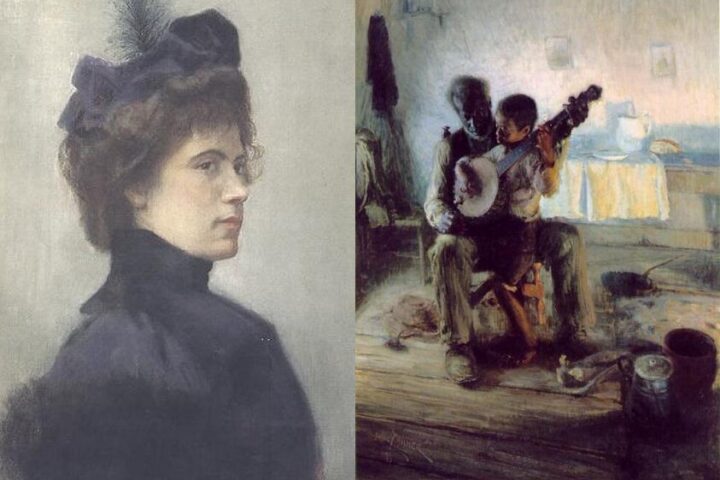

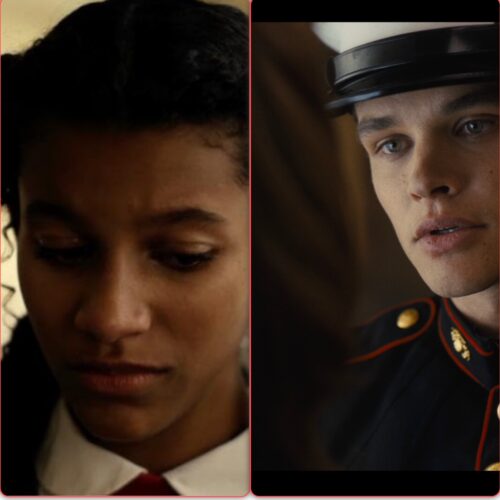

8. We also love your black and white faces; some of them emanate an air of sadness. Could you tell us more about them?

These are also drawn on negatives, so again rely on colour inversion. With these I wanted to challenge notions of race and identity. ‘Black’ vs ‘white’ is one of the most immediate and deep-seated dichotomies the world has created about race, and one that is steeped in mythology and lore. I wanted to flip that, to make black faces white, and white faces black.

9. We finally saw some white sculptures. What are they made of? What do they represent?

The ceramics were inspired by a trip I'd gone on to the India/Pakistan border with my family as a child. That trip was the closest I have ever been to my family's ancestral home. During the visit I was given a large fossil as a gift by a member of the border security forces who patrol the region. Its shape and form, its deep 'veins' are so rich, and the natural beauty of this ancient object drives home just how recent the troubles facing the desert region it came from are.

This also led to a fascination of studying rocks and formed a habit of mine to always collect rocks, stones and minerals from wherever we travel to (much to my husband’s frustration).

This also spurred me on to work with more tactile materials, in this case, natural clay. Each piece has lines running through them, one of which is in cardinal red. This was done to depict how some lines, borders or lands are naturally and beautifully formed – like the ones in the desert fossil – and how these stand in contrast to the blood-red lines that humans, and their politics, create.

Form-idea.com London, 1st September 2019 - Interviewed by Pierre Scordia and Annie Clein

Version française publiée sur le site de Mediapart.

Rewati Shahani: https://www.instagram.com/rewatishahani/

Map of Israel/Palestine

Map of Israel/Palestine

India

India

Hi like to talk to you🙏

To contact the artist: studio@rewatishahani.com