Opera Review: Giant Is a Haunting Meditation on Consent and Medical Ambition

Sarah Angliss’s new opera reclaims the story of Charles Byrne, confronting the disturbing legacy of scientific progress built on human exploitation.

A Fairytale Turned Nightmare

Sarah Angliss’s new opera Giant, which premiered at this summer’s Aldeburgh International Festival, is a haunting exploration of medical ethics and the concept of consent—a subject deeply resonant in our time. The opera delves into the life of Charles Byrne, the so-called “Irish Giant” of the 18th century, who reportedly stood over 7 feet tall (2.31 m), with some accounts claiming he was even taller.

At the heart of Giant is Byrne’s fraught relationship with the surgeon John Hunter, a man who offered friendship and medical assistance—but with deeply troubling motives. Hunter’s interest in Byrne was not only scientific; he sought to acquire Byrne’s body after his death for dissection, a prospect the young man found terrifying. Byrne made explicit efforts to avoid this fate, attempting to ensure his burial at sea. Yet Hunter ultimately obtained his body, an act that speaks volumes about the imbalance of power and the absence of consent.

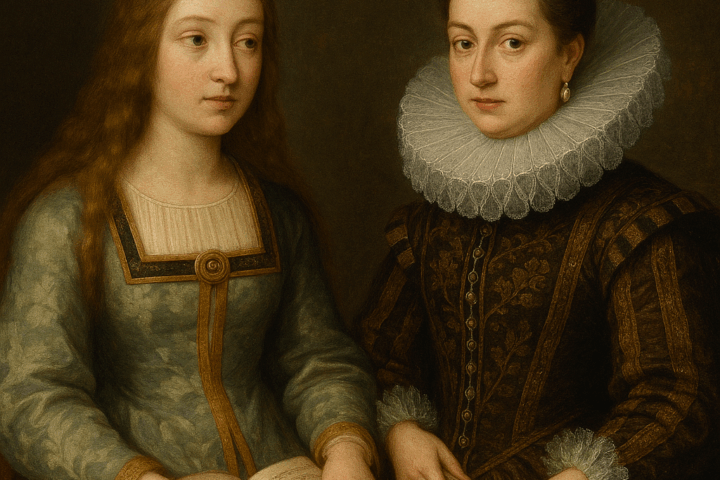

The opera examines the chilling intersection of scientific ambition and human dignity. It moves between two worlds: the curiosity shows—dubiously labeled “freak shows”—where Byrne earned his living, and Hunter’s anatomical laboratory, where bodies were routinely dissected in the name of knowledge. While Hunter offered relief for Byrne’s physical ailments, the offer was laden with conditions. Byrne’s instincts proved right: the help came at the cost of his autonomy.

This theme—how medical advancement has so often relied on the exploitation of vulnerable bodies—echoes another unsettling chapter in medical history. Modern gynecology, for instance, owes many of its foundational practices to Dr. J. Marion Sims, who established the first hospital for women in the United States and pioneered several surgical techniques. But his achievements were built on experiments performed on enslaved women—without anesthesia and without consent. These women, considered property, had no legal right to refuse. A statue once erected to honor Sims has since been removed, a public recognition of the unethical foundation of his legacy.

In Giant, Angliss raises difficult but necessary questions: When does the pursuit of scientific knowledge cross a moral line? At what point should a physician’s humanity override the drive for medical progress? And how do we reckon with the achievements of those whose work was made possible by the suffering of others?

By invoking the tragic story of Charles Byrne, Giant forces us to confront the uneasy truths at the root of both historical and modern medicine—truths that remain as urgent today as they were centuries ago.

The opera, written for five voices and performed on 18th-century instruments, tells this haunting story with striking beauty and emotional depth. At times, Giant feels like a bewitching, heartbreaking fairy tale—only here, the role of the wicked witch is played by medical science itself. Poet Ross Sutherland’s libretto draws the audience into this complex moral tug-of-war, where Dr. John Hunter’s actions can be condemned, yet his motivations are disturbingly understandable.

Angliss’s score is masterful in its ability to elicit empathy for both characters. Through vivid musical phrasing and nuanced vocal writing, she reveals the humanity and inner conflict within each of them, making it difficult to see the story in black and white.

Echoes of The Elephant Man

At moments, the opera also seems to evoke David Lynch’s The Elephant Man, another tale of a man—Joseph Merrick—born with a severe genetic disorder and exhibited in “freak” shows before being rescued by a compassionate doctor. Merrick lived the rest of his life in relative comfort at a London hospital. Yet, even in that story of apparent redemption, a troubling parallel emerges: after Merrick’s death, his body was dissected and preserved—against his explicit wishes for a traditional burial.

The echo between Byrne and Merrick’s stories underscores a central theme of Giant: the persistent failure to respect the bodily autonomy of those deemed different, even when society claims to be acting in their best interest.

A Companion Piece in Contrast

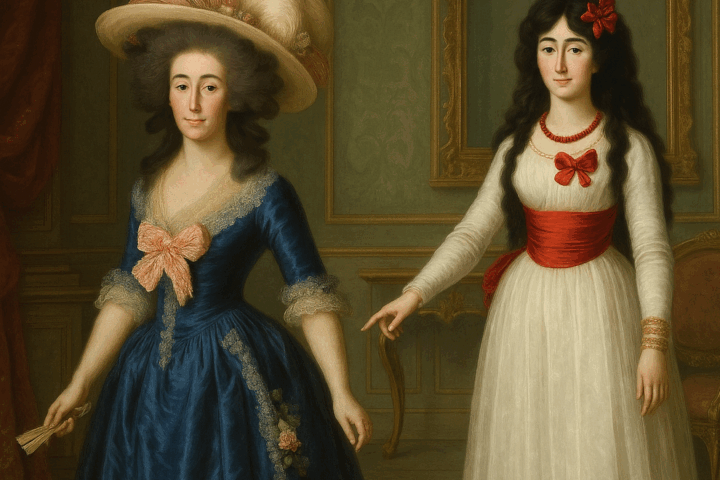

The opera Giant would make a compelling companion piece to Penny Black’s poignant play Mariedl: Selfies with a Giantess, which explores the life of Maria Fassnauer—known as Mariedl—often considered Charles Byrne’s female counterpart. Born nearly a century later in South Tyrol, Fassnauer also grew to an extraordinary height. But there, the similarities largely end. Unlike Byrne, Fassnauer appeared to possess a much greater degree of agency. She toured Europe, reportedly earned a considerable fortune, received a marriage proposal, and, most significantly, was allowed to rest in peace—buried intact.

By contrast, despite Charles Byrne’s desperate efforts to ensure a dignified burial—requesting his body be sealed in a lead coffin and submerged at sea—his wishes were ultimately denied. John Hunter, determined to possess Byrne’s skeleton, paid a large sum to acquire his corpse. It remained on display for over two centuries, only finally removed from exhibition in 2015.

Have We Really Changed?

Reading about the tragedy of Byrne’s life in the same week that a young, exceptionally tall Asian basketball player was signed to the NBA, one might be tempted to believe that society has evolved. Today, those born different often have far more control over their lives. That young athlete is likely to become a millionaire, a global celebrity, his height no longer a source of exploitation, but of admiration and profit.

And yet, the question lingers: has our gaze really changed? There may be no sinister doctor lurking to claim his body, but are we not still paying to stare—only now in stadiums instead of freak shows? Is he celebrated for his humanity, or merely consumed as a spectacle of difference? He won’t be denied a proper burial, but his image will be monetized, plastered on jerseys and merchandise worldwide.

Have we truly come so far? Or do the trappings of progress merely mask the same old instincts?

- Black Queer Voices

- Opera Singer & Singing Coach: Helen Astrid

- Opera like you’ve never known it

- A Touch of Shiatsu – An Oriental Approach to Bodywork and Well-being

- Crash Landing On You: A Wonderful Korean Soap Opera