Visions of Queerness | By Beverly Andrews

Sebastiane & A Life in Four ChaptersWith the number of LGBTQI-themed film projects increasing, it’s fascinating to look back at queer-themed films of the past, as well as the pioneering directors who made them. By creating this work, they helped pave the way for today’s vibrant crop of films.

This summer, London’s British Film Institute screened two queer classics—two of the most significant gay films from the 1970s and 1980s—and watching them makes it clear just how far we’ve come.

A Queer Pioneer

Derek Jarman is perhaps one of the most significant queer directors of the last century. His body of work, produced before his life was tragically cut short by AIDS, is especially remarkable given the hostile, politically anti-queer environment in which he created it.

One of his most notable early features, co-directed with Paul Humfress, is Sebastiane (1976). This homoerotic retelling of the life of Saint Sebastian—a Catholic martyr and religious icon—is striking in both form and content. The film is entirely in Latin, lending it a timeless, ritualistic quality, and in many ways, it prefigures Jarman’s later Caravaggio, which is widely regarded as his commercial breakthrough.

Yet Sebastiane is no less a significant cinematic achievement. Its lush and sensual reimagining of the Roman soldier’s life serves as a powerful metaphor for the persecution of the queer community—particularly in the United Kingdom, where Jarman lived and worked. During much of his career, the country was gripped by conservative politics under Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, whose government introduced Section 28—a law that prohibited local authorities from “promoting homosexuality.”

This legislation blighted the lives of an entire generation of lesbians and gay men in Britain and remained in effect until 2000, overlapping with and shadowing much of Jarman’s creative life.

Seen in this context, Jarman’s 1976 feature feels both refreshing and groundbreaking. He depicts the events that lead to Sebastiane being stripped of his rank and exiled to a desolate island. Once there, Sebastiane is expected to serve with a small regiment, but he refuses, choosing instead to devote himself to his newly embraced faith: Christianity. These acts of defiance result in his torture and, ultimately, his execution.

Yet in death, Sebastiane becomes a figure of reverence—the soldiers who killed him drop to their knees, overcome by the realization of what they’ve done, and begin to worship his broken body. It’s not difficult to grasp Jarman’s message: despite the hostility the gay community faced at the time, they would endure, they would resist, and in doing so, they would leave behind a lasting legacy.

Dark Masculinity

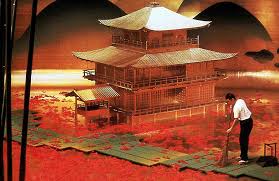

The other film featured in this BFI season was Paul Schrader’s Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters, a poetic and visually striking exploration of the life of Japan’s first truly international author, Yukio Mishima. A man of contradictions, Mishima’s sensational death by ritual suicide—seppuku—has long overshadowed his literary legacy. He hoped that his dramatic final act would trigger the restoration of the Emperor as Japan’s political leader, a goal that ultimately went unrealized.

With its hypnotic Philip Glass score, Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters seeks to present the man in full, not merely as the sum of his final day. Schrader divides the film into four thematic chapters and moves between two timelines: the events of Mishima’s final 24 hours, and key moments from his past that shaped his worldview and obsessions.

The film also subtly addresses his queerness—something that Mishima’s family has long resisted acknowledging. They even denied the filmmakers the rights to Forbidden Colours, his most overtly gay novel. Nevertheless, Schrader conveys Mishima’s complex sexuality through visual symbolism and suggestion. One of the film’s most telling moments comes when Ken Ogata, who plays Mishima, gazes longingly at a painting of Saint Sebastian, clearly captivated by the saint’s beauty and martyrdom. It’s a moment of quiet revelation—one that prefigures the writer’s own death, steeped in ritual, performance, and a haunting pursuit of purity and transcendence.

Paul Schrader, the director of Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters, is perhaps best known as the screenwriter of the legendary Taxi Driver, as well as the writer-director of American Gigolo. Both films explore a kind of tortured, isolated masculinity—a recurring theme in Schrader’s work. In Mishima, he returns to this obsession, delving into the psyche of a man caught between aesthetic ideals, personal demons, and political fanaticism. The film becomes a meditation not only on Mishima’s life and death, but also on the performance of masculinity itself—rigid, self-destructive, and bound to codes of honor and shame.

Sebastiane and Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters, taken together, highlight a time when filmmakers struggled to tell truly queer stories, often pushing against the cultural and political constraints imposed upon them. And yet, despite these challenges, they created two landmark works—bold, lyrical, and unapologetically personal. These films not only stand as powerful artistic statements from their time, but also as enduring inspirations for future generations of queer storytellers.

Sebastiane was screened as part of the BFI’s Big Screen Classics series, while Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters featured in Shifting Layers: The Film Scores of Philip Glass, a season celebrating the composer’s iconic work for cinema. Though part of different strands, the pairing of these films underscores a shared spirit of defiance and vision. Both Jarman and Schrader—working across cultures and decades—crafted bold, deeply personal films that broke new ground in representing queer identity and inner conflict. Despite the constraints of their time, they produced enduring works that continue to resonate and inspire.

- Saint Germain’de Bir Türk Kadını

- UNA MUJER TURCA EN SAINT GERMAIN

- FLARE 2022

- Black Queer Voices

- Le dilemme ukrainien : européisme ou homophobie ?