With art historians now more willing to explore the careers of pre-20th-century non-European artists, names previously ignored are being discovered. Two such artists are Annie E Walker and Henry Ossawa Tanner, both African American artists of the late 19th century who would achieve their greatest success in Europe and leave a lasting legacy.

A pioneering female artist’s journey

Annie E Walker

Annie E Walker was born in Flatbush, New York in 1855 and originally trained to be a teacher. She married a rising African American lawyer, and together with him, she moved to Washington, D.C. It was there that she discovered art. After taking a series of art classes, Walker applied to and was admitted to the prestigious Corcoran School of Art. Sadly, once the administration discovered she was black, the invitation to enroll was withdrawn. Despite the fact that Walker enlisted the help of the famous abolitionist Frederick Douglas, who tried to intervene on her behalf, the college stood by its refusal. Walker was not deterred though, and travelled to New York, where she applied to the prestigious Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art and was admitted.

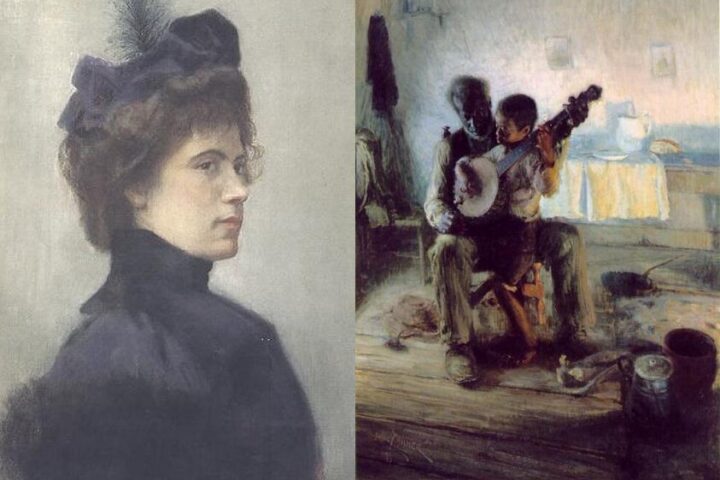

After completing her training there, Walker sailed for Paris, where she became the first recorded African American woman to study at the prestigious Académie Julian. It was in Paris that Walker found her artistic voice. She was chosen to present her work in the 1896 Paris Salon, and the work she produced showed a young artist with a remarkable ability to capture the small moments in people’s lives. Her watercolor Studies of a Man in 16th Century Dress is a delight, as is her more famous La Parisienne, also painted in 1896. La Parisienne is simply mesmerizing and shows a stylishly dressed young Parisian woman captured in a moment of time. Both works point to a gifted artist with a promising career ahead of her. Unfortunately, this was not to be. Once Walker returned to America and sought to balance her roles as both wife and artist, she found it impossible and subsequently suffered a nervous breakdown. It was a breakdown from which she would never fully recover and remained housebound for the rest of her life. Walker left behind a small number of paintings that hint at what could have been, had she not been forced to choose between domesticity and an artistic career.

The first African American star painter

Henry Osawa Tanner

Henry Ossawa Tanner was the first African American painter to achieve global success, winning an honorable mention at the Salon of 1896. For a Black man born when slavery was still a reality for many African Americans, his achievements are astonishing.

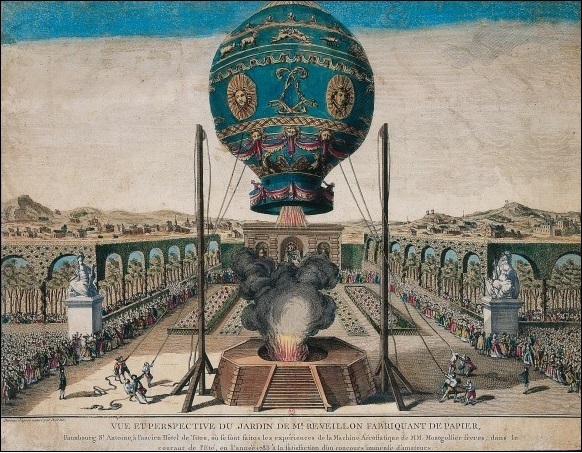

Tanner was born four years after Walker, in 1859, during the volatile years in America that would eventually lead to the catastrophic Civil War. Tanner’s family was relatively middle class. His father, Benjamin Tucker Tanner, would become a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the first independent Black denomination in the United States. Both of Tanner’s parents were free, and, unusually for the time, his father had a college degree. Tanner grew up with an intellectual curiosity and, as a result, would go on to become the class valedictorian of his year. During this time, Tanner experienced a moment that would transform his life. Walking in a park with his mother, he came across an artist who was painting a landscape. Later, Tanner would state that this was the moment when he decided to become a painter. In 1876, Tanner attended the historic Centennial Exposition, where he saw the African American artist Edmonia Lewis’s pivotal sculpture, The Death of Cleopatra. It’s interesting to note that many in the African American religious community were shocked by it.

Tanner sought art tuition but was rejected by many at first because he was Black. He was also increasingly pressured to follow his father’s path into the church, something he refused to do. After becoming seriously ill during a summer job, his parents relented and encouraged his artistic endeavors. Despite this, Tanner continued to struggle on his own until he was eventually encouraged to apply to the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. There, he was tutored by the inspiring Thomas Eakins, who encouraged his use of color.

It was there that Tanner would become the victim of a racist attack. Joseph Pennell, a fellow student who was representative of many who studied with Tanner, wrote some years later, “There has never been a great Negro painter…” The irony of this statement is that Pennell wrote it after Tanner had already triumphed in Paris. The incident that would haunt Tanner for the rest of his life occurred when his easel was taken out of his room, dragged into the street, and he was tied to it as if crucified. It was an event Tanner would never forget. In many ways, it became the catalyst for him leaving both the academy and the country, deciding to try his luck in Paris.

Escaping the restrictions of American racism in France

Travelling to France, Tanner also attended the Académie Julian. The atmosphere there was radically different from that of his college in the US, and he found acceptance from both students and staff. It was there that Tanner came into his own, both as a man and as an artist. Travelling periodically between his home in the US to see his family and France, Tanner contracted a serious bout of typhoid, forcing him to remain for a while in the States. While there, Tanner painted a series of works depicting African American life; one of the most famous is The Banjo Lesson, a beautiful depiction of a father (or possibly grandfather) giving a young boy a music lesson. The painting, in many ways, could be read as a metaphor for the wisdom of one generation being handed down to another.

He would remark later that those who had painted African Americans in the past had only done so in order to portray comic caricatures of Black lives. Tanner, however, sought to counter this with his own portrayals of African American life from an informed perspective. He wanted to show African Americans as not only shaped by the racial hostility they invariably faced but also shaped by family warmth and respect. Tanner, encouraged by the positive reception The Banjo Lesson received in America, submitted it to the Paris Salon, where it won high praise but did not sell, with many citing the fact that French critics struggled to understand the context of African American life represented in it. Another painting from this period is the beautiful The Thankful Poor, depicting a father (or grandfather) seated at his table with a child immersed in prayer. It would be one of the first of many depictions by Tanner of spiritual contemplation, a theme he would revisit continuously throughout his career.

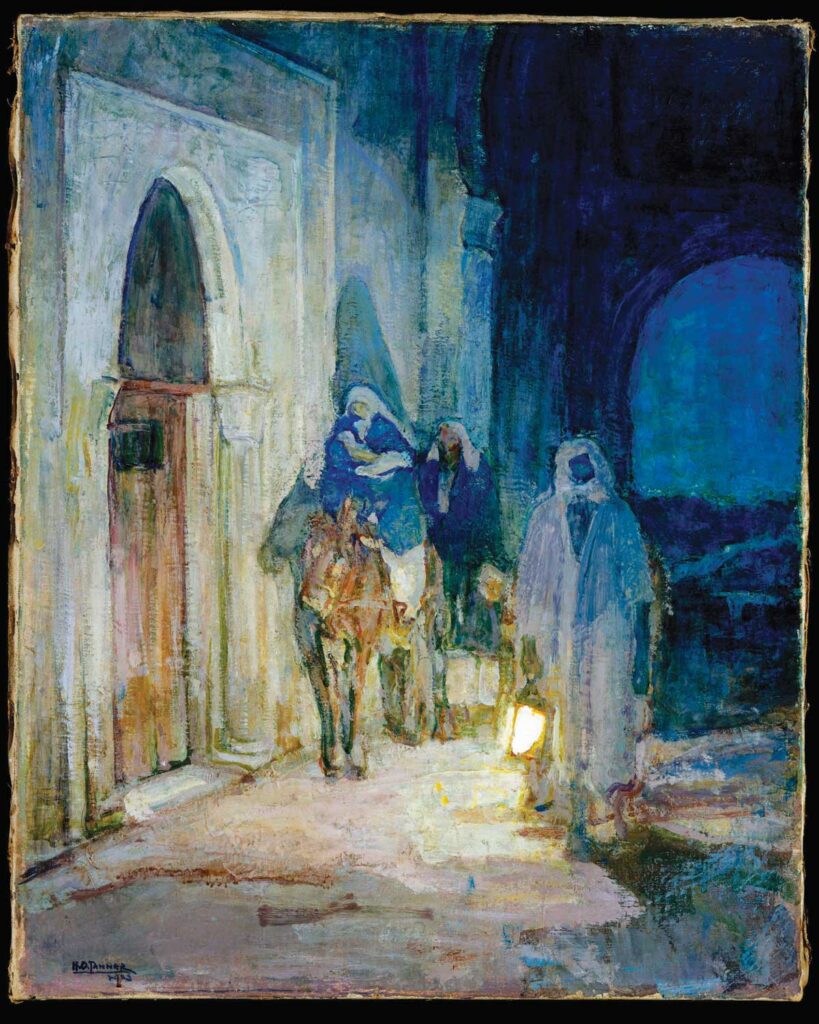

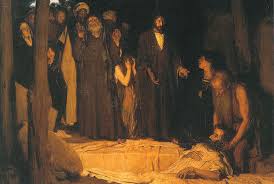

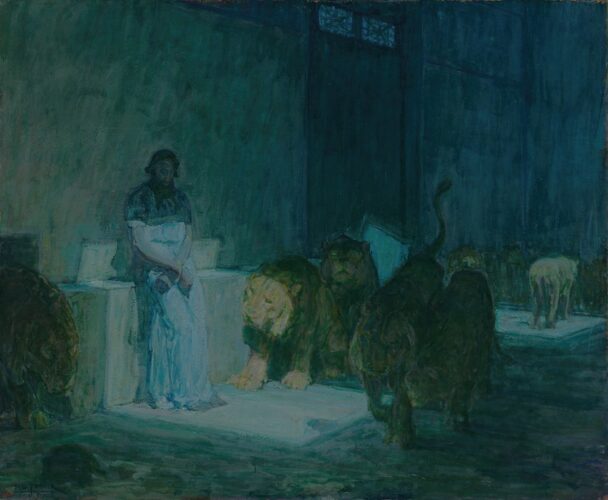

Perhaps because of his father’s religious influence, Tanner turned to faith as his next subject. But instead of depicting biblical scenes, he chose to focus on the land of faith itself. Influenced by Caravaggio and Rembrandt, Daniel in the Lion’s Den became the first painting in the series. Hung prominently, the painting earned Tanner his first honorable mention. He continued in this vein, working on a depiction of the Raising of Lazarus. Friends believed this would be his breakthrough and raised money for him to visit the Holy Land, which he accepted. Tanner traveled to ancient mosques, the pyramids, Jerusalem, and the Dead Sea. The images he saw would inspire much of his work for years to come.

While traveling, he eventually received a letter informing him that The Raising of Lazarus had been awarded third prize at the Salon in Paris. The letter also conveyed that the French government wished to buy it. Less than forty years after the abolition of slavery, an African American artist had achieved the French government’s highest artistic honor. This marked the height of Tanner’s career.Tanner married, settled in France, and raised a family there, finally able to call France his home. However, he was deeply traumatized by both World Wars, a trauma that made it difficult for him to paint afterward. It was almost as if, once he lost faith in man, he also lost faith in the power of art. Yet, if you look at his early work now, you can see the humanity he brought to it, along with the warmth, love, and, perhaps above all, the hope he infused into everything he painted.