Spanish Women Who Made History

They were not merely daughters, wives, or consorts of powerful men—they were women who carved their own place in history. Urraca I of León ruled as queen in her own right, fighting fiercely to maintain her authority in a male-dominated world. Beatriz Galindo, known as La Latina, dazzled the court with her mastery of Latin, educating queens and princesses with a humanist vision ahead of her time. Luisa Roldán, a master sculptor, defied expectations and poverty to become the first woman named court sculptor to the Spanish crown.

Their paths were turbulent, their achievements hard-won, and their legacies enduring. Through war, scholarship, and art, they left their mark—not as shadows behind powerful men, but as leaders, thinkers, and creators in their own right.

In this series, I want to highlight some of the women who earned their place in Spanish history on their own merits. Not because they were mothers, wives, or daughters of someone important, but because their actions and achievements secured them a place in the collective memory. It’s true that some—by being mothers, wives, or daughters—already had a certain status, as is the case with queens, princesses, and women from great lineages, but those we will cover from that group are the ones who stood out in those roles, surpassing the men and women of their rank.

This is not a list of exemplary women; these are real women, with virtues and flaws, often controversial, but all determined to overcome the many social obstacles to do what they set out to do. Except in some cases in the late 19th century, we can’t exactly call them feminists, but rather women who, individually, refused to accept the limitations imposed by the societies they lived in. And they did it so well that their lives are still remembered. Some of them, however, could be considered part of the proto-feminist movement known as La Querella de las Damas, a debate sparked by the poet Christine de Pizan in the early 15th century. She authored The Book of the City of Ladies, in which she defended women against the misogyny of her time. Through fictional interviews with great women in history, she argued that supposed female inferiority was not natural, but rather the result of limited access to education. It is interesting to note that Isabella I of Castile had a French copy of The City of Ladies in her library.

This selection of women from Spanish history begins in the 12th century with the indomitable Urraca I of León and ends with the three great Galician women of the 19th century: Rosalía de Castro, Concepción Arenal, and Emilia Pardo Bazán. I chose to end there because from that point on, the number of women making history multiplies, as feminism takes shape and more women gain access to education.

In today’s first group of women, my goal is to show the variety of challenges and fields in which they excelled—well ahead of their time and outstanding in their roles. We begin with Urraca I of León, the first reigning queen of the Iberian Peninsula, who refused to be ruled by others and exercised power herself, even though it meant spending her life at war, often leading her troops in person. The second is Beatriz Galindo, a scholar, lady-in-waiting, Latin teacher, and advisor to Queen Isabella I of Castile. And lastly, Luisa Roldán, a sculptor who achieved the title of royal sculptor under King Charles II—an accomplishment no other woman, before or since, has matched.

In future instalments, the women will be grouped more by the fields in which they stood out than by historical period—queens and princesses, patrons of the arts, writers, adventurers, courtesans, heroines, and great consorts.

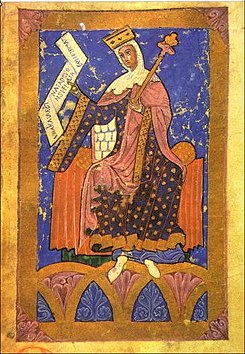

Urraca I of León

(1081–1126)

Urraca was the first woman to reign in her own right over the kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula. She became queen of León and Castile at a time when León remained the more powerful of the two, and her reign marked the second significant attempt to unify them.

She rose to power due to the absence of a legitimate male heir. Her father, Alfonso VI, despite five legal marriages, failed to produce a son of lawful birth. At one point, he even named as his successor an illegitimate son born of his concubine, the Moorish noblewoman Zaida—but the boy died at just fifteen. With no other option, Alfonso designated his daughter Urraca as heir. The nobility accepted her on one condition: that she remarry at once, as she had recently been widowed from her first husband, Raymond of Burgundy.

Alfonso chose her second husband—against her will—to be Alfonso I of Aragon, known as “the Battler.” Their wedding took place in 1109. Had the union succeeded, it could have brought about the consolidation of the Christian kingdoms of the peninsula. But it quickly devolved into conflict. Alfonso of Aragon sought to wield authority in Urraca’s kingdoms, as permitted by their marriage treaty, but Urraca consistently resisted, even siding with his enemies. Their marriage descended into a prolonged civil war between rival factions. It was ultimately annulled in 1114 on the grounds of consanguinity—they were second cousins. Although Urraca’s allies petitioned for the annulment, it was Alfonso who, embittered and childless, repudiated her.

Urraca I, Queen of Léon and Castile

Urraca I, Queen of Léon and Castile

She was not a great queen—if greatness is measured by peace and prosperity. Her reign was turbulent, marked by relentless conflict: with her husband, with rebellious nobles and cities, and against the advancing Almoravids. But Urraca’s true significance lies in her personal strength and defiance. She insisted on her sovereign right to rule independently, and governed as any king of her time might—taking lovers, bearing illegitimate children, and managing her territories as her personal domain.

Contemporaries called her “the Reckless,” a title that has endured in the historical record. Bold, combative, and fiercely protective of her authority, she often acted with exceptional courage. One such moment came in 1115, when the people of Santiago de Compostela, alongside Bishop Diego Gelmírez, rose against her and besieged her inside the unfinished cathedral. While the bishop fled disguised across the rooftops, Urraca stood her ground. She was captured, beaten, humiliated—pelted with stones and filth, stripped of her clothes. Even so, she managed to calm the mob with promises of reform. Once freed, she raised her troops, returned to the city, and brutally crushed the rebellion, breaking every promise she had made.

After her marriage was annulled, internal warfare continued to plague the realm. Urraca died in 1126 at the age of 44, reportedly in childbirth, at the castle of Saldaña. She was succeeded by her son from her first marriage, who took the throne as Alfonso VII of León and Castile.

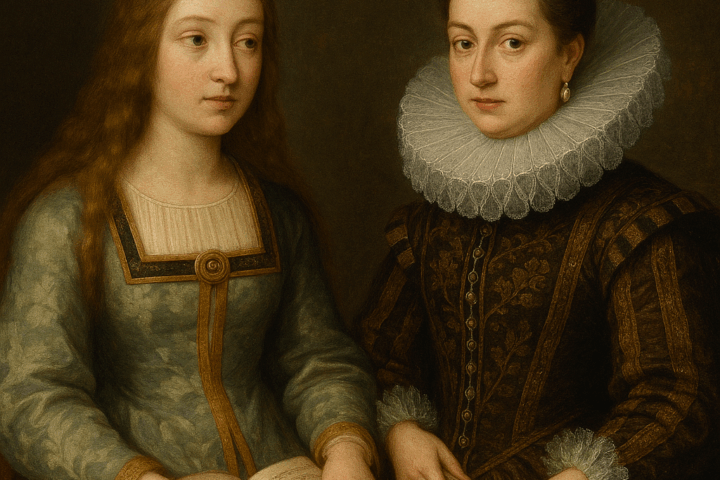

Beatriz Galindo, “La Latina”

(1465–1534)

Beatriz Galindo was born into a noble family that had fallen on hard times. From an early age, her parents recognized her sharp intellect and steered her toward a religious life, enrolling her in grammar studies at academies affiliated with the University of Salamanca. There, she displayed an extraordinary talent for Latin. By the age of sixteen, she was translating classical texts and speaking and writing Latin with such precision and fluency that she astonished her contemporaries. Her reputation quickly spread throughout the kingdom, earning her the nickname La Latina.

In 1486, at the age of twenty-one and on the verge of entering a convent, Beatriz was summoned by Queen Isabella I to teach Latin to the ladies of the royal court. Setting an example herself, the queen—who had not received a classical education—attended the lessons alongside them.

Beatriz also oversaw the education of several royal princesses who would go on to become queens: Joanna of Castile, Isabella and Maria of Portugal, and Catherine of Aragon, future queen of England. Under her guidance, they received an exceptional education, rare for women of the time.

A strong friendship developed between Beatriz and Queen Isabella, who came to value her counsel deeply. Beatriz’s summons to court marked the end of her aspirations for monastic life. In 1495, the queen arranged her marriage to Francisco Ramírez de Madrid, an artillery officer who had distinguished himself in the conquest of Granada. As a dowry, she received the extraordinary sum of 500,000 maravedís. This alliance also served a political purpose: strengthening a circle of loyal, reform-minded nobles at a time when consolidating power against the traditional aristocracy was crucial.

After becoming a widow in 1501, Beatriz wished to retire from court life, but the queen persuaded her to remain. It was only after Isabella’s death in 1504 that she withdrew to the Palace of Viana in Madrid. In retirement, she continued the religious and charitable work she and the queen had shared a passion for—founding hospitals and convents dedicated to the care and protection of vulnerable women.

Beatriz Galindo was a distinguished humanist, held in high esteem by her peers and students alike.

Luisa Roldán

(1652–1706)

Luisa Roldán: A Singular Figure in European Art

Luisa Roldán stands as a rare exception in the history of Spanish and European art. Before the 19th century, there is record of only one other female sculptor across all of Europe: the 16th-century Italian artist Properzia de Rossi.

That her work was recognized and celebrated during her lifetime is a remarkable achievement. The painter Antonio Palomino praised her skill, stating that her work was on par with that of her father, the renowned Sevillian sculptor Pedro Roldán. Indeed, her talent led her to be appointed court sculptor to both Charles II and Philip V—an extraordinary distinction.

Luisa trained in her father’s workshop, where all the children, sons and daughters alike, contributed. While her siblings focused on tasks like polychromy and gilding, Luisa gravitated toward sculpture itself. She quickly distinguished herself with her skill in both design and execution, becoming one of her father’s most trusted collaborators.

At 19, she wished to marry fellow sculptor’s apprentice Luis Antonio Navarro de los Arcos. Her father opposed the match, but Luisa boldly took the case to court—and won. The couple established their own workshop in Seville, where she was the principal artist, though her husband signed the contracts. Their relationship with her father appears to have improved, as evidence of later collaborations suggests.

Luisa’s work belongs to the tradition of religious imagery at a time when art aimed to humanize devotional figures, imbuing them with greater expression and movement. Her sculptures are noted for their refinement and a gentle sweetness that made them highly sought after. The distinctive personalities in her figures’ faces have led some scholars to speculate that they may have been modeled on people from her own life.

After Seville, the couple moved to Cádiz, and later to Madrid, hopeful that Luisa could secure a position at court. She aspired not only to artistic recognition but also to financial stability. In 1692, she achieved a milestone: she was named royal court sculptor and began signing her works with this prestigious title. Yet despite her acclaim and the steady flow of commissions, the economic rewards never followed. The Spanish Empire was in decline, and even the royal household was known for paying poorly and late.

Luisa wrote numerous letters to the palace, pleading for basic support—housing, food, and financial aid—lamenting her inability to provide for her family. Meanwhile, her father’s business continued to flourish in Seville. It remains unclear why she never returned—perhaps she valued official recognition over financial gain, or perhaps family tensions played a role. Her marriage proved difficult, and her husband never rose to prominence in his craft.

Following the death of Charles II in 1700, Luisa petitioned the new monarch, Philip V, to retain her role as court sculptor—a request that was granted. She held the title until her death in 1706, remaining the first and only woman in Spanish history to achieve such a position.