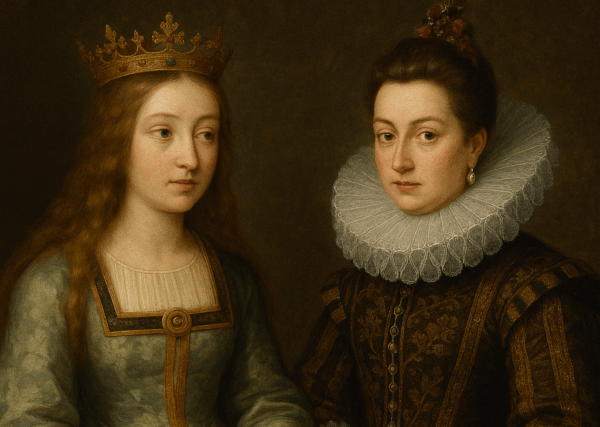

Together, these two Isabellas—separated by a century but united in their force of character—embody two faces of power: one forged in the crucible of war and reformation, the other shaped by peace, diplomacy, and culture. Each, in her way, helped shape the destiny of empires.

Isabella I of Castile: The Architect of a New Spain

Isabella I of Castile (Madrigal de las Altas Torres, 1451 – Medina del Campo, 1504) reigned as Queen of Castile from 1474 until her death in 1504. Her legacy is inseparable from that of her husband, Ferdinand II of Aragon. Together, their dynastic union laid the cornerstone for modern Spain, forging a centralized monarchy and a unified national identity.

Although ruling their respective kingdoms independently, Isabella and Ferdinand’s reign was a joint project of nation-building. They consolidated royal authority over a fragmented and often rebellious nobility—an essential step in the dismantling of feudal power. Their accomplishments were sweeping: the union of Castile and Aragon, the conquest of Granada in 1492 (ending centuries of Muslim rule), the establishment of a centralized legal code, economic reforms aimed at strengthening the state, and the creation of the Santa Hermandad, a kind of internal police force to maintain order.

Religious unity became one of Isabella’s most controversial pursuits. Her reign saw the expulsion of Jews, forced conversions of Muslims, the persecution of non-Christians in Granada, and the establishment of the Spanish Inquisition—an institution that formalized and expanded religious intolerance in the name of state stability.

Despite the harshness of her policies, Isabella’s reign was not without humanitarian vision. She insisted on education for her daughters and ladies-in-waiting, founded religious and charitable institutions for the poor—especially women—and was adamant about providing proper medical care for her troops. Her early laws seeking to protect Indigenous peoples in the Americas, though largely ineffective in practice, also reflect a complex moral compass.

Her rise to power reveals much about her formidable character. Her brother, King Henry IV—derided as “the Impotent”—was viewed as a weak monarch, both politically and personally. Suspicions about the legitimacy of his daughter, Juana, opened the door for Isabella’s ascent. She secured recognition as heir, then married Ferdinand of Aragon in secret, defying both her brother and the Church (as the marriage required papal dispensation). When Henry disinherited her in response, she asserted her claim to the throne upon his death in 1474.

At just 23, Isabella declared herself queen, setting off a five-year civil war between her faction and Juana’s. Ultimately triumphant, Isabella confined Juana to a convent in Portugal, thereby securing her dynasty’s hold on the throne.

To this day, Isabella I of Castile remains one of the most polarizing figures in Spanish history—a monarch whose achievements and actions continue to inspire admiration, debate, and reflection.

Isabella Clara Eugenia: Sovereignty with a Softer Hand

Isabella Clara Eugenia (Palace of Balsaín, 1556 – Brussels, 1633), daughter of Philip II and Elisabeth of Valois, governed the Catholic Southern Netherlands from 1598 to 1621, and remained as governor under Spanish rule until her death in 1633. Known for her diplomacy, empathy, and cultural patronage, she represented the more conciliatory face of Spanish rule abroad.

From birth, she shared an unusually close bond with her father. Philip II once declared that no son could have pleased him more. She worked closely with him in matters of state, assisting in bureaucratic tasks, translating official documents, and even sitting on royal councils—an exceptional role for a woman of her time.

A central figure in Habsburg marriage diplomacy, Isabella Clara Eugenia was once considered as consort to various European thrones—including the Holy Roman Empire, the Duchy of Brittany, and even France. Eventually, her father arranged her marriage to Archduke Albert VII of Austria. As part of this alliance, Philip II ceded rule of the Southern Netherlands to the couple in 1598, implicitly recognizing the independence of the Protestant North.

Under their joint rule, the region experienced an era of peace and renewal. The Pax Hispánica, a 23-year respite from continental warfare, fostered economic growth and cultural flourishing in Flanders. The ducal couple strengthened the identity of the Southern Netherlands, quelled anti-Spanish sentiment, and championed the Counter-Reformation using the arts as a political tool. This golden age of the Flemish Baroque saw the rise of figures such as Peter Paul Rubens, Pieter Brueghel the Younger, and Wenceslas Cobergher.

After Albert’s death in 1621, Isabella Clara Eugenia, who had no children, continued to govern as a royal appointee of her nephew, Philip IV. Though the territory returned to direct Spanish control, she worked tirelessly to preserve regional autonomy and stability.

In both Spain and the Netherlands, she is remembered as a wise and benevolent ruler—one who balanced imperial interests with a genuine commitment to the well-being of her people. Through diplomacy, cultural patronage, and steady leadership, Isabella Clara Eugenia left a legacy of enlightened governance amid a time of deep division.

Isabella of Castile

Isabella of Castile