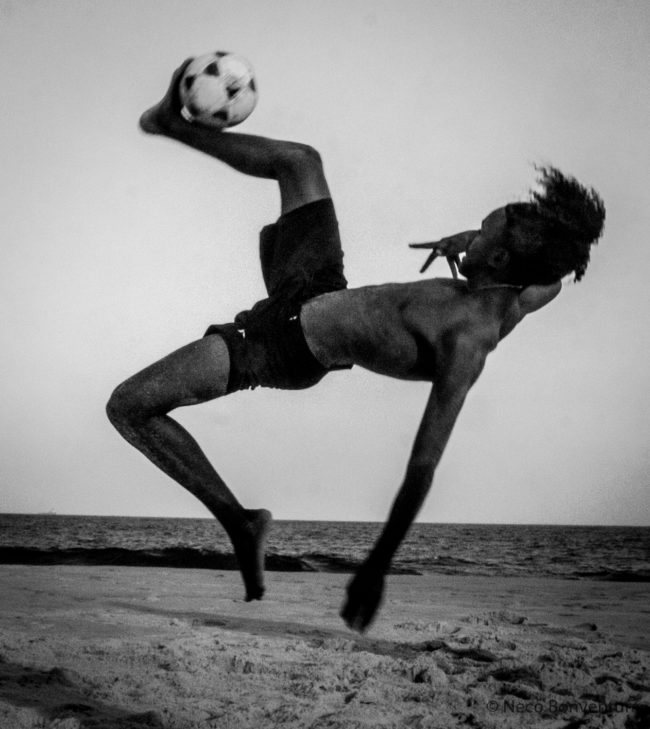

Neco Bonventura

If you speak Portuguese, you will quickly realize that Neco is very Carioca: he has a guttural accent, distinct from that of São Paulo in the economic heartlands, which is more nasal and melodious. Surprisingly, Neco is not Carioca but from the North, Belem (the largest city of the state of Pará). He loves his roots, a mix of Native Amazonian animist and Portuguese Catholic cultures. It is important to recognise that Catholics in Brazil are far more tolerant than the fast-growing Evangelical churches [1] which meddle in politics by backing the far-right President, Jair Bolsonaro.

I met this artist at a Carioca party in the Historical Centre one Friday night ten years ago. I saw him again the next day as we had realised we were neighbours: we both lived in Arpoador, a lovely neighbourhood located at the junction of Copacabana and Ipanema beaches. We spent a few afternoons on Ipanema Beach, talking as we sipped refreshing beers and caipirinhas. Even though our behaviour might have appeared superficial, our conversations were less so. It is undeniable that Brazilian people are warm and cheerful, but beneath the surface lies struggle and suffering, especially in Rio. In this paradisical setting violence prevails, mainly due to three factors: social injustice, racism and drug trafficking. Brazil is no different from any other Northern or Southern American country in that it is ruled by people of European descent who dominate politics and the social scene and to a certain extent the cultural, even if cultural diversity has long been the norm in Brazil.

The dark side of Rio de Janeiro

In 2012, from my window I watched the Federal Police launching a major helicopter assault on Cantagalo, the favela overlooking Copacabana; the government wanted to “clean up” the city before the Olympic Games of 2016 – following the success of the 2007 Pan American Games. From my apartment, I could hear gunshots as if we were at war.

In Rio de Janeiro, the close proximity of the safe neighbourhoods of the filthy rich to poor and dangerous favelas seems surprising. In fact, before tunnels were built in order to open up this part of the bay, the wealthy families of Leblon, Ipanema and Copacabana required their house employees to live close by. Thus, their staff had no choice but to settle on the stunningly beautiful surrounding mountain slopes.

©Neco Bonventura

©Neco Bonventura

On one occasion, Neco told me that the cleaning lady where he was working ten years before, had had seven sons, six of whom had died violent deaths; this grieving mother wished she had had only daughters… Such terrible violence is a real curse for underprivileged Brazilians. Furthermore, the disastrous way that the Covid-19 pandemic has been managed by the Federal Government in Brasilia (Brazil has one the highest death rates in the world) has had dramatic consequences on the population, especially in the favelas.

The beauty of Rio

But despite its flaws, Brazil is still an amazing place to live. The artist Neco loves his country: the people with their joie de vivre, their friendliness, their music; the diversity, the breathtaking landscapes and the beauty of the Brazilian Portuguese language. Even though he no longer lazes about on Ipanema beach, Neco goes there to photograph Cariocas, capturing moments of beauty and joy in this fleeting life.

When asked if he prefers photographing men or women, he replied without hesitation: “women” because they are more expressive and even a little provocative when they look at the camera, making for great pictures.

©Neco Bonventura

©Neco Bonventura

He appreciates what Ipanema represents of Brazil: the Bossanova music and its artists who denounced the military dictatorship. Neco wishes that his city were more colourful, and if he could, he would paint the houses in the favelas many different shades! He loves the two mountains O Morro do Dois Irmãos (“The Mount of the Two Brothers”), the Sugarloaf and Corcovado, because unlike in São Paulo which has become a seemingly endless concrete forest, Rio de Janeiro is a megapolis where nature and beauty abound.

©Neco Bonventura

©Neco Bonventura

Instagram: @necobonaventura | @newsformidea

How did the experience of meeting Neco Bonventura affect you?

Regard Telkom University