Afghanistan – Tile Giant

By Simon Urwin

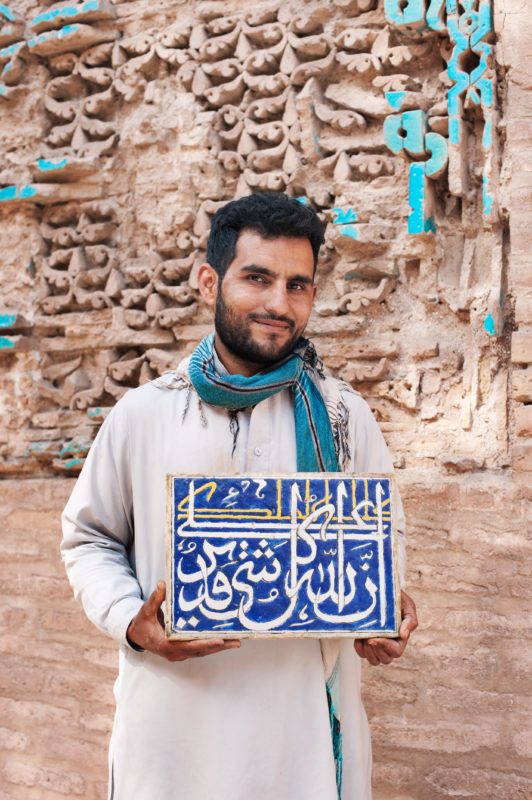

“Working with ceramics every day is like a form of worship for me, it helps me feel closer to Allah,” Omid announces proudly.

This is not the kind of line you’d ever hear from a Topps Tiles’ employee, I think to myself.

Omid the tile maker - loose crop

Suddenly, a shaft of heavenly light breaks through the roof and illuminates the mud-brick room where we sit chatting, the walls charred inches-thick with centuries of smoke. No wonder the world of tiling makes one feel all religious-y here.

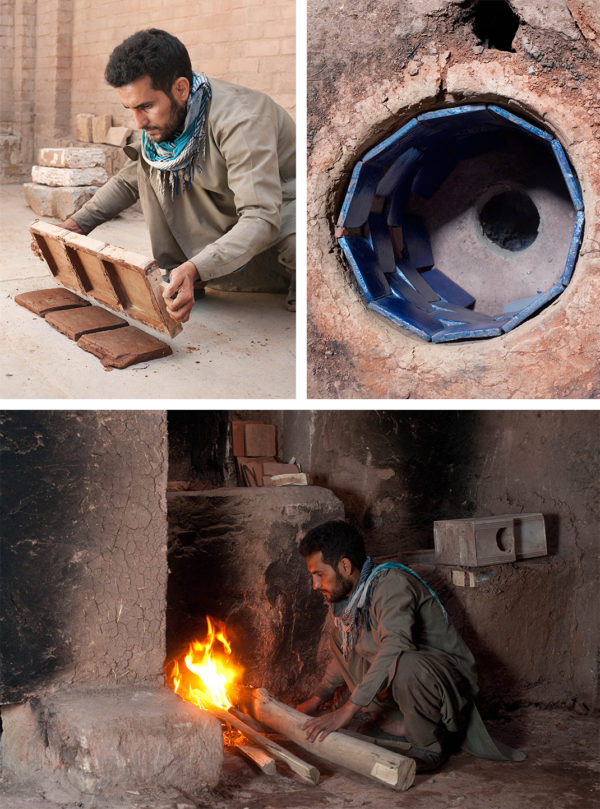

I’ve come to the Tile Factory of Herat, tucked away to the side of the city’s glorious Friday Mosque in the north west of Afghanistan. Built some 1,000 years ago, it’s widely believed to be the oldest tile factory in the world. Barely a detail has changed in more than a millennia.

Inside the workshop where the oven is located.

The factory’s chief tile maker and painter is Omid Karimi, a man on a mission to bring forth the best tiles in God’s universe, his ceramic creations having recently restored to glory some of the holiest buildings not just in the country, but in all Islam’s domain: the Shrine to Hazrit Ali; the minarets of Gohar Shad; the dome of the Khoja Abu Nasr Parsa in the marijuana-growing region of Balkh, to name but a few.

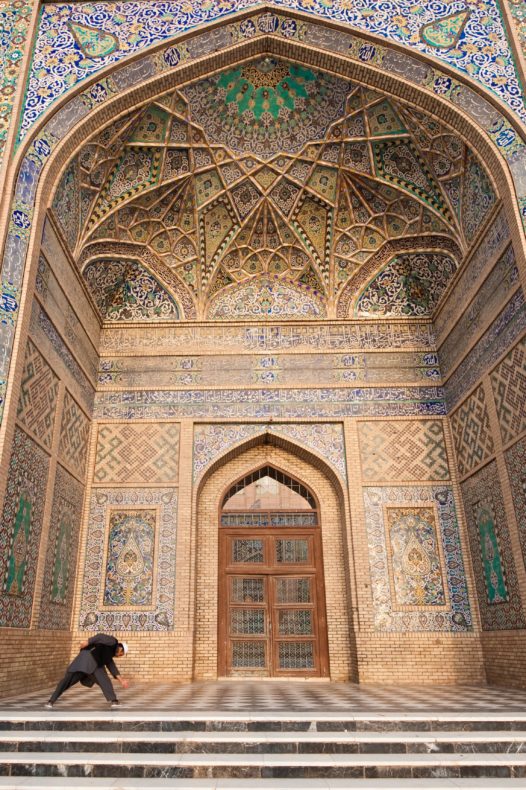

Omid's workshop is within the complex - and his work has featured on the mosque.

Always busy with renovations in this bruised and battered land, I follow Omid about his work to a shaded courtyard, still bearing the remains of turquoise tiles from the times of the Timurid – that ancient dynasty, who along with the Mughals, were the first to make religious buildings in Afghanistan sing with vibrant colour.

There, over the hours that follow, much sweat and toil is spent as the 31 year-old Herati draws from piles of riverbed clay, throwing and moulding a mountain of raw tile squares, all by hand. “I can put all my heart, soul and spirit into this because I have a deep physical connection with what I do,” he tells me, earnestly.

Stoking the ancient tile oven with logs of dry white willow to raise the perfect temperature, Omid is adamant that the age-old techniques of the Timurids are still the best. “Modern machine-made tiles do not last for long. The colours fade easily, they are only good for indoors, they are not fit for the outside where the world will see them.”

Once baked, the tiles are then decorated by his talented hand with a palate of just seven colours, two of which are Omid’s preferred option for both visual impact and worshipper wellbeing. “Koranic verses were once written in turquoise so it’s a good colour to use to protect a building and the people inside from the evil eye. It can even stop a mosque from falling down,” he reassures me. “I like lapis lazuli very much too. Long ago it was used to highlight all the religious inscriptions which were always painted in white, adding to the power of the messages. It focuses the eye perfectly.”

As an artist of considerable importance in Afghanistan, I ask Omid if his tiles bear a personal hallmark – something like Toulouse Lautrec’s monogram or Banksy’s stencil signature – or if he prefers his artistry to be anonymous. “I am not famous nor do I want to be,” he assures me. “When I die, the next generations will not know me either, but they will see me without realising it in my beautiful buildings, which hopefully Allah will protect from war and earthquakes so they will stand forever. That will be my legacy.”

FORM-Idea.com London, 16th December 2016.

Exterior detail including minaret which has featured Omid's work

Omid's workshop is within the complex - and his work has featured on the mosque.

Simon Urwin

Simon Urwin