EVERYTHING YOU WANT TO KNOW ABOUT INVERTEBRATES

Interview with Vladimir Blagoderov

Principal Curator – Invertebrates, National Museums Scotland

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of Vladimir Blagoderov and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of National Museums Scotland.

What is your job at the National Museums?

National Museums Scotland is one of the oldest and largest collections in the UK; it contains exceptional artefacts such as Lewis chess or Concorde, but for me the real strength of its collection is in the natural history specimens. Out of 12.5 million objects in the museum, almost 10 million are animals, fossils or minerals. Invertebrates (animals without bones, like jellyfish, corals, worms, molluscs and insects) are the largest part of the collection, counting more than 6 million specimens. My task as the head of this part of the collection is to provide preservation of it in perpetuity as well as its use for exhibition, education, and research.

Have you ever been out in the field collecting specimens?

This is one of the main tasks of any curator and researcher, and certainly the most enjoyable. During my time at the Palaeontological Institute, Moscow, I carried out a lot of field work in Northeast Asia – Yakutia, Buryatia and the Far East – primarily looking for fossil insects, but also collecting more recent specimens of fly. Since then I did some collecting in North America, Europe and South Africa, but nowhere near as much as I would have liked. Although I described quite a few species from the tropics, I have never been collecting there. Hopefully that will change soon.

What sparked your passion for invertebrates and insects?

Three things. Firstly, a relatively pristine environment. When I was a child my town, though very close to Moscow, was surrounded by almost untouched woods. My great-grandparents had a small house and an orchard. I spent a lot of time outdoors, much more than children nowadays. Secondly, I was an avid reader, and I was fascinated by science. I probably read most of the popular science books published in the Soviet Union between 1950-1980, at least everything I could find in the city library. And last, but not least, a good biology teacher who always found time for all my questions and encouraged me to ask and to think.

How important are they for our ecosystem?

Extremely. People rarely realise that more than 80% of all living species on Earth are invertebrates. Our biosphere simply would not function without them. There would not be any milk because cows could not digest grass without the help of single-cell animals, protozoans; there would not be any grass or any plants apart from lichens or mosses because earthworms and other soil animals would not help to form proper soils; our lakes and seas would be muddy and rotting because bryozoans, clams, small crustaceans and insect larvae would not filter waters; the whole earth surface would be covered by bodies of dead animals and tree trunks because there would not be anyone to consume them quickly and efficiently. And this is just for starters.

Could insecticides and GMO be a threat to them or even wipe them out?

This is a series of related questions. Insecticides are natural and artificial compounds used to kill pests. Unfortunately, insecticides are rarely selective, and together with harmful invertebrates, such as pests and parasites, can also kill the useful ones, for example pollinators, such as bees and hover flies. But pests are created by human activity. For example, farm fields or glasshouses are very simplified natural ecosystems, where a complex food network of hundreds and thousands of species of plants and animals is replaced by a single species (crop). This makes it very vulnerable. If an insect that normally feeds on this plant is accidentally introduced onto the field, in the absence of natural enemies it starts to breed uncontrollably. Therefore, pests have an advantage in numbers and can more easily develop tolerance to insecticides than insects in agricultural ecosystems.

The other method to fight pests is by knowing their biology. We can employ a species of parasitic wasp whose larvae feed on caterpillars that eat our vegetables, or release irradiated males of mosquitoes, so the females will not be able to lay fertile eggs after mating. Biological methods of control may be more laborious or expensive, but are often more effective in the long term.

Genetically modified organisms (GMO) can be used as a biological control of pests. Crop plants can be modified to be resistant to a particular pest and harmless to other insects and animals, including humans. For an expert, there is no controversy about using GMO. It is important to remember that all organisms, including all plants are genetically modified. What farmers of the past have been doing through slow random selection for hundreds of years we can now achieve in a lab in a matter of weeks. The mechanism is exactly the same as in nature, just faster.

Would insecticides or GMO wipe out all insects if we invent a super-pesticide? Hardly. Humankind would die out before the complete elimination of insects, because Earth’s ecosystem would collapse. Some species of insects and other organisms would survive this crisis, but not humans. Therefore, a careful selective control of pest species is needed.

How does global warming affect invertebrate population?

Invertebrates are poikilothermal organisms, which means they cannot maintain constant body temperature like birds and mammals. This makes them particularly sensitive to changes in temperature. Even more importantly, invertebrates are incorporated in a complex food web in ecosystems, and dependant on micro-habitats. Climate change, as with any environmental change, affects flora and fauna directly. Result can be various – from changes in behaviour, sex ratios, or distribution to complete local and global extinction, and, ultimately, collapse of the ecosystem. The most recent example is the Great Barrier Reef, which can no longer be salvaged.

What is currently the biggest threat facing invertebrates?

Loss of habitats as a result of human activity. Global warming is just one aspect of it, together with pollution, deforestation, expansion of agroecosystems. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) recently listed almost 600 species of invertebrates, but even more, perhaps hundreds of thousands, went extinct before we even discovered them as a result of deforestation in Amazonia or Borneo, for example.

Have there been some great conservation successes where an endangered invertebrate has been brought back from the brink of extinction?

One of the examples is the Lord Howe Island stick insect which has been considered extinct for 80 years but is now being successfully bred in Melbourne Zoo.

Do you feel that whilst people are moved by the plight of cute animals such as pandas, endangered invertebrates tend to be ignored?

Flagship species, such as the giant panda, blue whale, or monarch butterfly help to attract public attention and mobilise support for conservation issues. These resources are being spent on protection not just for cute bunnies, but entire ecosystems, particularly in biodiversity hotspots.

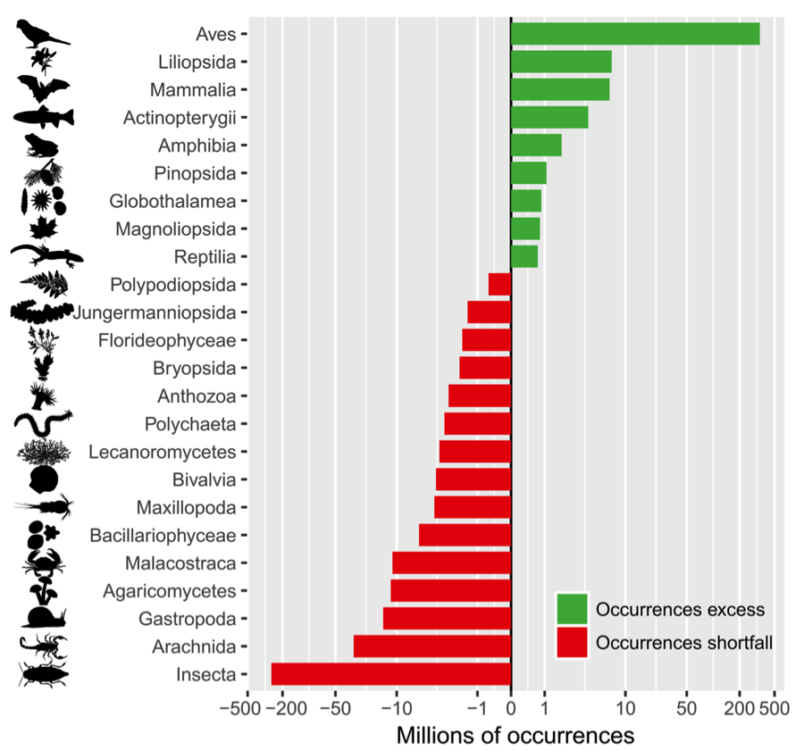

On the other hand, public misunderstanding of invertebrates, their importance, ubiquity, and beauty, leads to chronic underfunding of research on them. This taxonomic bias caused by societal preferences is particularly acute when it comes to insects. I see our mission as scientists to educate people, explaining the importance of all living beings on the planet.

Are we still discovering new species?

About 20,000 new species of animals are described every year, although more than 1,500,000 species have been named already. Estimations of the total number of species on Earth vary between 3,000,000 and 15,000,000 species (the latest study estimates a number of animal species alone as high as 163,000,000). My contribution is very modest – I described ~210 new taxa, including approximately 150 new species.

Have you contributed to the fascinating field of biomimicry? If so, in what way?

Indirectly. In 2011 Martijn Timmermans, a postdoc at the Natural History Museum, studied Papillo dardanus, African swallowtail, or “flying handkerchief” butterfly. Females of this species are unusually polymorphic (varying in shape and coloration of wings), mimicking up to 14 other species of butterflies. I was a head of an imaging lab in NHM at the time, and SatScan, an imaging instrument we developed for insect collections, helped Martijn to get images of more than 3,500 specimens very quickly.

Could Brexit have an impact on your work and on National Museums Scotland?

It will, undoubtedly. In the short and medium term the economy will plummet, which will result in further cuts to the public sector. Severing relationships with the EU will terminate many, if not all, European programs funding research in the UK.

How many languages do you speak? How many can you read?

Unfortunately, I am fluent only in Russian and English. I know a few bits of Latin and ancient Greek, as every taxonomist does, since names of organisms ideally should be derived from these languages. Reading professional literature in most languages now is much easier; algorithms of automatic translation are becoming more and more advanced.

Is it important to speak different languages for your work?

Although at the moment English is almost a universal language of science, being able to speak other languages really helps. You can establish more rapport with your colleagues and sometimes even scientific terminology is not universal, knowing this, misunderstandings can be avoided.

Do you miss your homeland, Russia?

No, I miss people, not places. People are the same everywhere.

Is being Russian useful in creating bridges in terms of working collaboration between Britain and Russia?

Unfortunately, there are not a lot of funding opportunities for collaboration between British and Russian scientists. But when it happens, an understanding of the cultural differences between the two countries can be crucial for success.

After spending so many years in London, how do you find life in Edinburgh?

Absolutely amazing. Edinburgh combines all the attractions of a big city and comforts of a small town, not to mention the warmest people in the world.

A silly question: if you were an insect or invertebrate, which would you be?

I’m rather individualistic, which excludes all social and colonial animals. I have lived in extremely different societies through all stages of my life; that should relate me to animals with distinct life stages spent in diverse environments, such as insects with complete metamorphosis (holometabolous). My mother and my family helped me a lot through my younger days. That probably makes me a solitary bee species, for example a carpenter bee.

Finally, can you give us a feel for a typical day at work at the museum?

It varies. Some days are happy and full of insects and research, the others are just a bureaucratic routine. But usually it’s the mix:

8:30 – meet volunteers and discuss their work for today

9:00 – meet a scientific visitor, provide him with desk space, equipment, materials and specimens necessary for his research

9:30 – looking for lost notebooks, where data on one of the most important collections of British beetles is contained. Notebooks not found this time, but three more boxes of unprepared material are discovered

10:30 – maintenance company finally repaired an alcohol pumping system that did not work since 2014

11:00 – time to book flights for a conference in November. Have to coordinate with my colleague from London

11:15 – report for the Board of Trustees. Everything that has been done by the section in last quarter goes there.

12:30 – a visitor needs to take images of some specimens, but does not know how to use the equipment. Training session

13:30 – a journal sent reviews of the manuscript submitted last year. Replying to reviewers’ comments and correcting manuscript to send it back as soon as possible.

15:00 – finally some time to work with the collection! About 100 specimens of long-beaked fungus gnats (Lygistorrhinidae) from French Guyana were sent to me by my colleague; the material contains at least four species new to science

17:00 – should be time to go home, but what about all the e-mails I received today?

19:00 – Titan arum, the largest and stinkiest flower on Earth started to bloom in the Royal Botanic Garden of Edinburgh. Since it does it at night, the garden will be open for visitors till midnight. Have to go there and help my colleagues, tell the visitors about insects and maybe collect some flies and beetles attracted by this magnificent plant.

Interviewed by Annie Solomons and Pierre Scordia.FΩRMIdea London, 15th September 2017.

Papilio dardanus - one species, many forms

Papilio dardanus - one species, many forms