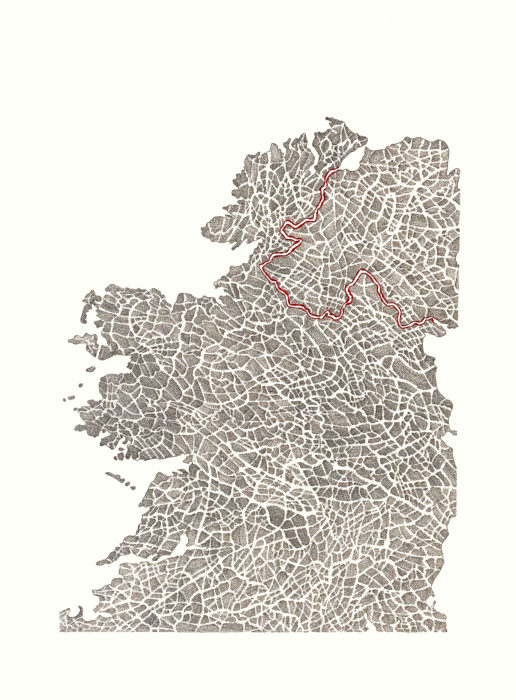

Lost lives in Northern Ireland

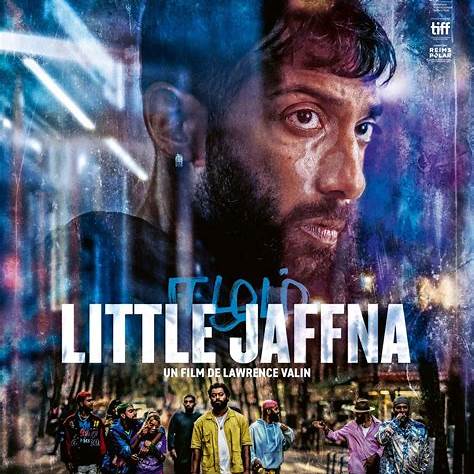

This year's BFI London Film Festival kicked off in the country’s capital with its usual delightful mix of mega stars standing alongside indie unknowns. The festival's eclectic mix of the famous and as yet undiscovered, has made it a favourite among many since the selection of films screened appears to be based solely on quality rather than a film’s box office potential. But away from the headline grabbing debuts and the star-studded premiers was a little discussed but, in many ways, far more important feature for our troubled times. The film's title is taken from a book by the same name called Lost Lives. This documentary looks at the heart-breaking legacy of The Troubles, a euphemism for the sectarian conflict which ran for over thirty years in the United Kingdom’s Northern Ireland.

The Troubles was a conflict which engulfed the Protestant and Catholic communities living there. A conflict which dragged on for over thirty years and is estimated to have cost the lives of 3,600 people, most recently the life of young journalist, Lyra Catherine McKee. The book of Lost Lives was written by five journalists and took over seven years to write; it sought to document every death which occurred as a result of the conflict. For the film several sections of the book are read by many of the country's most renowned Irish actors including Stephen Rea, Liam Neeson and Kenneth Branagh and between them, they read stories which document many of the deaths which occurred during this tragic time. Their voice overs are accompanied by footage of the time, footage which shows a region descending into a de facto civil war.

Some of the most heart-breaking moments of this harrowing film are the accounts read of those who died who had no direct connection to any of the fighting factions but were simply in the wrong place at the wrong time. Like the account of one of the very first murders to take place during The Troubles, that of a nine-year-old child who was merely sleeping in his family's home when a bullet was fired on the street below that somehow ricocheted and instead of hitting its intended target made its way through the child’s bedroom window killing him instantly as he slept. A tragic casualty of a rapidly escalating conflict which at its height resulted in several hundred deaths a year.

Another account was connected to the practice of the random kidnapping of individuals to somehow repay a blood debt, a practice which was carried out with savage brutality during the height of The Troubles. In the film one story is told of a young woman so devastated by the random murder of her fiancé killed in one such kidnapping that a month after his death she takes her own life leaving a heart-breaking letter for her family simply saying she just could not find a way to reconcile herself to her fiancé’s murder.

Another account read was that of a Protestant paramilitary member who served a long sentence for one such kidnapping and murder. He recounts how he had no idea who the man was until the hood the kidnappers had used to cover their intended victim’s face was removed and he saw standing in front of him his best friend. Before he could say anything, the man was shot dead. Subsequently members of the group served long prison terms for his murder. The Protestant paramilitary member was eventually released from prison and went on to become a powerful voice for peace. But what the public did not see was his constant internal struggle to find some way to forgive himself for the murder. Ultimately, he was never able to do this and in the end he too committed suicide. The film concludes with a read account of the recent murder of journalist Lyra McKee, an innocent bystander and another victim of this unending saga who simply as a journalist wanted to document a sectarian riot; a clarion call for peace so that future generations are not scarred by this conflict.

Although Lost Lives, the book and the film document the loss of life in both the Catholic and Protestant communities one can clearly see the constant strain both communities lived under. A complete inability for anyone living there to live a normal life, be it an avoidance of open spaces which were likely to be bombed or trying to avoid the watchful eyes of those who might inform on members of their own communities or simply making sure never to go out alone at night so as to avoid the possibility of being a retaliatory kidnapping target.

As the UK approaches the most significant election for generations the outcome of which could dictate how and if the United Kingdom leaves the EU, with a worst-case scenario being the prospect of the return of a hard border (one which would require military patrols) Lost Lives paints a devastating portrait of two communities torn apart by sectarian violence and is in many ways a needed response to all those MPs who advocate for a Hard Brexit and the dismantling of The Good Friday agreement (an international agreement which lead to a ceasefire and relative peace in the region). They would say that somehow The Good Friday agreement has outlived its usefulness. Anyone who says this should be forced to watch Lost Lives.

London, 17th November 2019. @BeverlyAAndrews