PARTITION VOICES

By Beverly Andrews

Divisions

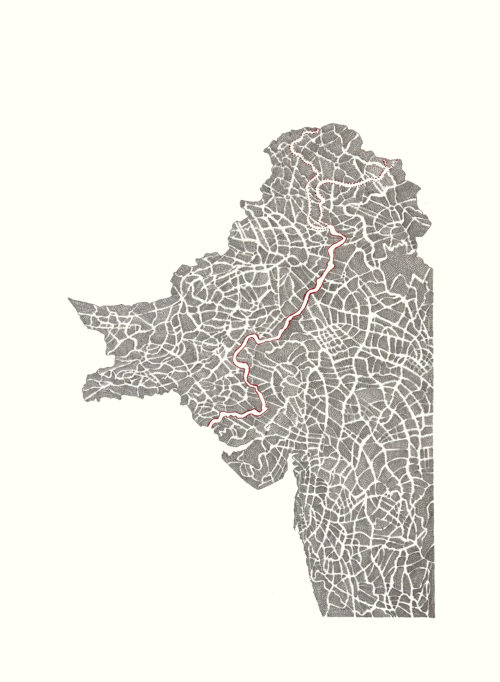

Almost all countries throughout the world have experienced at least one defining historical moment which in many ways defines generations to come. For those which have emerged from the colonial grip it can be the moment at which they achieved their independence. For others it can be the moment when regional differences can no longer be papered over and they then erupt into conflict. In America it is perhaps their civil war which in many ways is their defining moment, it’s a war they still seem to be fighting. While for India their defining moment would of course be partition, a division imposed on India and Pakistan by the retreating British government. One which ultimately cost the lives of an estimated two million people, while also leaving another ten to twelve million homeless. A partition which also resulted in another war, one in Bangladesh, when that country subsequently fought for its own independence. Three separate countries carved out of an originally whole. A gaping wound which lingers to this very day, a wound which continues to haunt generations even now. At this year’s Jaipur Literary Festival, held virtually due to the ongoing to pandemic, historical authors Aanchal Malhotra, Kavita Puri, Sam Dalrymple, Vazira Fazila-Yacoobali discuss this painful historical event.

Living consequences

Aanchal Malhotra who chaired the talk began by stating that it was important that partition is not simply viewed as an historical event but one with “living” consequences. Vazira Fazila-Yacoobali highlighted this fact by recollecting her own personal story. Her aunt who lives in India is facing eviction and yet her mother in Pakistan, who desperately wants to help, cannot because of the regional division. A division which means that her mother cannot travel there and her aunt cannot come to live with them in Pakistan. Their personal tragedy is a living legacy of the tragedy of partition. Vazira states “It’s a political decision that I need to understand, a political decision which needs to be undone.” Variza’s book called The Long Partition highlights how this is not a fixed event lost in the annals of time but one which has continued to have tragic consequences.

Silences

Kavita Puri spoke of her dad who as a child lived through this terrible time, but he has chosen to remain silent about it. She pointed out that her dad was not unlike others from his generation who moved home in the immediate aftermath of partition and then moved again, in their case to the United Kingdom. Once here they simply, she said wanted to get on with their lives and not look back. And their children simply chose not to ask questions. She states “they had seen awful things, maybe things which happened in their families, dishonour, shame, these are hard things to speak of.” Kavita pointed out though that living in Britain there is also a collective silence, no one is really even taught about it. “This is a story of Britain but there is no public space to discuss it.” She pointed out that it was this which compelled her to explore it, she stated “partition is over seventy years ago, and if their stories are not discussed they will be lost.”

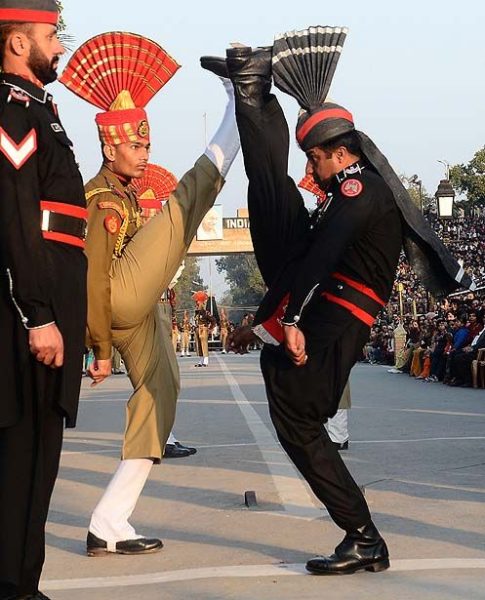

Borders

Sam Dalrymple, who is a British historian, but has grown up in India, is currently writing a book as well looking at partition but from an entirely different perspective. He has also worked on a separate project which seeks to connect those from the partition generation virtually with their childhood homes. He states “I first visited Pakistan in 2015 with remarkable ease, I applied for a visa in Delhi and being British received it quickly. I was struck by the complete disconnect between dialogue from each side. And when I went to university I had so many friends with grandparents who wanted to cross the border. So we decided to create virtual reality experiences for those who wanted to go back but could not, through our Project Dastaan. It is a peace-building initiative which examines the human impact of global migration through the lens of the largest forced migration in recorded history, the 1947 Partition of India and Pakistan. Lockdown though hit and we could no longer travel.” Sam though used the time during lockdown in 2020 to research even more about partition since so much of what we know about it is based on the experience of the Punjab ignoring the geographical effects on different parts of India.

Aandal points out the importance of Sam’s geographical project which gives ownership back to an older generation of their history. Pointing to the importance of it to a now elderly generation, for them to have a virtual experience of seeing the streets they once walked down as children or the villages they were born in could help heal wounds.

Breaking through the Silences

Kavita went on to point out while there were silences between the generations, that did not mean there wasn’t an internal dialogue “they didn’t speak about it, that doesn’t mean they don’t think about it”. She went on to say that this is particularly prevalent for women who may have been the victims of sexual violence so their experiences only live in their silences. Kavita continued and stated though that it was crucial for second and third generations to find a compassionate way to break that silence.

Sam also pointed out that it is not just those from the South Asian community who are living with their silences. He himself who is British but was brought up in India, never knew that his grandfather was a young British officer at the time of partition, someone who perhaps lost friends during the war but never spoke of it, nor would ever visit his family once they moved to India. It was a silence which was only broken the day before his grandfather died and the family found out that he had actually known India’s first Prime minister, Nehru. But in his silence he hid the horrors he had witnessed, which affected him for the rest of his life.

Vazira points out how growing up in Pakistan there was always a sense of loss. It was always apparent and harbours a deep psychological resonance. She goes on to point out that partition in itself is in many ways a colonial concept, to carve out countries from communities who have lived together for generations, multi faith communities who had found a way to cohabit. So in speaking about it, it may be an important way to highlight these communities’ deep fundamental connections. Maybe political borders have been imposed but the people can still find a way to on a humanistic level to connect in their hearts.

The discussion can be found here.

form-idea.com London, 21st November 2020.