Estimated reading time: 138 minutes

Making Sense of the World Around You

How as an artist do you make sense of a world in which at times you are made to feel invisible? That has been an ongoing challenge for black artists throughout the African diaspora. In the wake of George Floyd’s death that challenge took on a new urgency. The Hayward’s Gallery’s new show titled In the Black Fantastic offers a glimpse of how black artists throughout the world are approaching this challenge in ways that are simply dazzlingly. From surrealists, to Afro Futurists, to artists who simply defy categorization, the show is simply stunning and an event not to missed this summer.

Ekow Eshun, journalist and author, is the show’s curator, and he points out in the exhibition’s catalogue that it is the first art exhibition of its kind to exhibit the work of black artists who embrace myth and science fiction as a way to address racial injustice, while exploring imagined alternative realties. Eshun explains that this is not a movement or a rigid defining category so much as a way of seeing the world shared by the artists who grapple with racial inequalities by conjuring up new narratives of Black possibilities. The art is stunning, but it is also in line with so much that is surfacing from the community at large, be it the southern gothic imagery of Beyonce’s Lemonade, to the spectacular reach of Marvel’s Black Panther, to the thoughtful science fiction of the work of Octavia Butler. The show is less leading the way than simply highlighting an artistic exploration which is gathering pace.

The Artists

Before you even enter the Hayward you are greeted by an uncredited outdoor installation of a black woman’s legs under a waterfall. This nameless piece immediately alerts you to the fact that you are now entering a very different world. The first gallery room you arrive at displays the work of the acclaimed African American artist Nick Cave and his new commission called Chained Reaction. The piece consists of a series of interlocked hands cast from Nick Cave’s own which are suspended from the ceiling. From a distance they seem to symbolize cultural solidarity since the hands appear to be holding each other. But upon closer inspection the hands grasp is tenuous and you feel that with the slightest knock that grasp will fall away. Perhaps a metaphor for the fact that for many in the African diaspora no matter which steps you may take to create a secure life, it only takes one event (in America that could simply be one unforeseen traffic stop) for all of your hard work to collapse around you.

Further in this same gallery room you see Cave’s “Sound suits”, created in the wake of Rodney King’s filmed beating at the hands of officers from the LAPD. The footage of this beating, and the officers subsequent acquittal, would trigger the LA’s riots/uprising. The “Sound suits” Cave creates are futuristic in style and obscure the faces of those who wear them. By doing so they erase gender, race and class. They also act in way as protective armor against a world, which at times can be hostile to those viewed by the majority as the other.

Wangechi Mutu, one of several female artists, exhibited works with collages. The artist says that her work is “a way of destroying a certain set of hierarchies that I don’t believe it”. Muti creates beautiful pieces from natural materials such as soil, stones and shell from her many travels. The sculptures she creates reference the divine, feminine forms as well as our mythical guardians. She states: “They look like they are guarding me, guarding language and the earth that they’re made from”. Her master work in this gallery room would have to be her surreal film of a feminine sea monster who consumes all in her way and then excretes gasses that ultimately destroy her world. It’s not a stretch to see this as a metaphor about man’s unbridled consumption, which will if not checked, destroy us all.

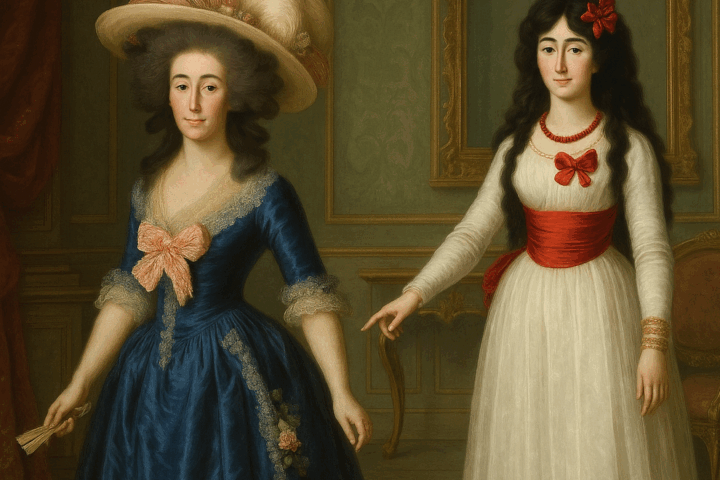

Wander further in the gallery and you will discover Lina Iris Viktor’s work, which are beautiful paintings that also draw on myth and legend. The series, A Haven, A Hell, A Dream Deferred, relates to the history of Liberia, a West African country founded in 1822 to resettle free-born and emancipated African Americans since it was felt by political leaders at the time (including Civil War President Abraham Lincoln) that a multicultural society in America was an impossibility. In this section the artist herself appears in the guise of the Libyan Sibyl, a prophetess of Greek myth who legend has it foresaw the transatlantic slave trade and was referenced at the time by several abolitionist groups in their fight to end slavery.

Hew Locke’s gallery room contains the sculptures of four bejeweled kings on horseback entitled the Ambassadors and a possible reference to black revolutionary figures such as Toussaint Overture, one of the leaders of Haiti’s successful revolution. The majestic sculptures are set against floor length photos of decaying traditional Guyanese homes, the native country of the artist’s father, Donald Locke, who is also an acclaimed artist. Whether the juxtaposition is a reminder of the fragility of power, or a context through which these revolutionary figures emerge from, is not made clear but what is clear is the sumptuousness of the work.

Entering the gallery room of the work of Rashaad Newsome and you can be forgiven for thinking that you entered a nightclub, since the electronic dance music being played is pulsating. That music is the soundtrack of Newsome’s film called Build or Destroy, a futuristic short which features a Blade Runner style landscape erupting in flames as a young beautiful black trans woman, who transforms into an AI creation, Vogues to the beat. Newsome describes this act of demolition as a destruction of a state of mind rather than an actual physical landscape. This state of mind, is rigid and outdated and only through its destruction can the world allow in a new more inclusive mind-set.

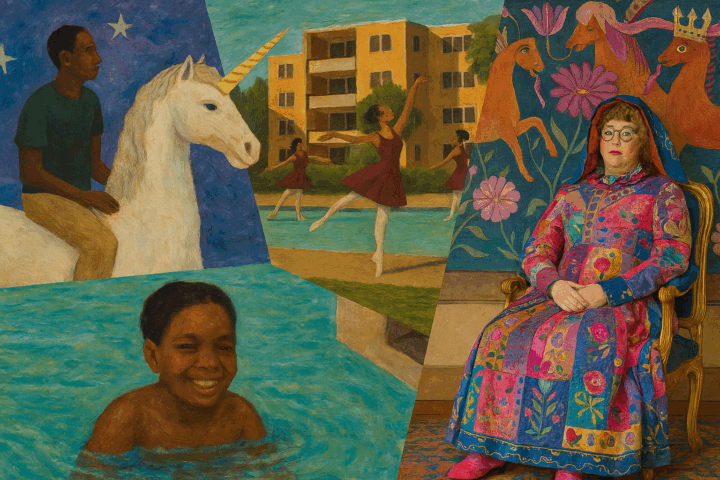

Further in the exhibit is the wonderful work of Turner prize award winner Chris Ofili who imagines scenes from European foundation myths, be they Homer’s Odyssey or The Annunciation. Ofili takes these stories and makes them sensual and alive. He doesn’t so much document them but rather reinterprets their meaning. It’s an area Ofili has explored throughout his career, taking stories such as these and recasting their narratives.

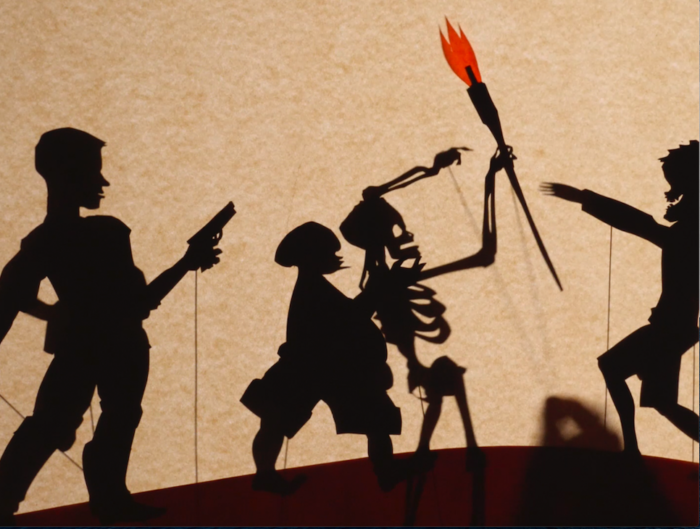

The African American artist Kara Walker uses cut paper silhouettes to craft depictions, rooted in American history, of sex and violence. Seen as one of the more controversial artists working today, Walker does not hesitate depicting the violence many within the African American community have historically faced. And the video shown here, Prince McVeigh and the Turner Blasphemies, is a case in point. The title is a reference to Timothy McVeigh, the bomber responsible for the infamous racist Oklahoma terrorist bombing, which killed one hundred and sixty-eight people including nineteen children, as well as the murder of James Byrd in Texas. The child-like nature of Walker’s film can be disarming and disturbing, but it makes total sense in the context of the message Walker’s work conveys, which is that sadly this violence directed at minority communities is so commonplace, to the point that at times it can almost feel like child’s play.

Spoken Word through a Futuristic Lens

This blockbuster exhibition is accompanied throughout its run with evening performances. The one I attended featured Ellah P Wakatama x Space Afrika x Alistair MacKinnon’s futuristic dub techno group’s soundscape that accompanied a selection of readings selected by editor Ellah P Wakatama, which explored the black experience through the lens of the fantastic. Not all the selections worked, but those that did were stunning and they included Chinua Achebe’s African classic When Things Fall Apart. A section of that work highlights the sense of isolation many feel when they immigrate to European countries, the sense of otherness that in some cases you never loose.

That evening also included an outdoor DJ whose mixes had the multiracial crowd dancing. The day was only marred briefly by a pair of overzealous security guards stationed at entrance of the Queen Elizabeth Hall. Despite the fact that the theatre was featuring a black event that evening, they appeared nervous about having so many black theatre-goers arriving and were checking tickets at the building’s entrance despite the fact that the foyer area is a public space with a public café and as such should be (and normally is) free to all.

The multi-racial crowds I saw that day who were eager to see both the exhibition and the evening event highlights how far for me British society has come. The overzealous security guards stationed at the door that evening highlighted as well how far though we still need to go.

In the Black Fantastic runs until the 18th September at London’s Hayward Gallery and will be accompanied by a selection of events in the evening check the Southbank website for further details.

©Chris Ofili

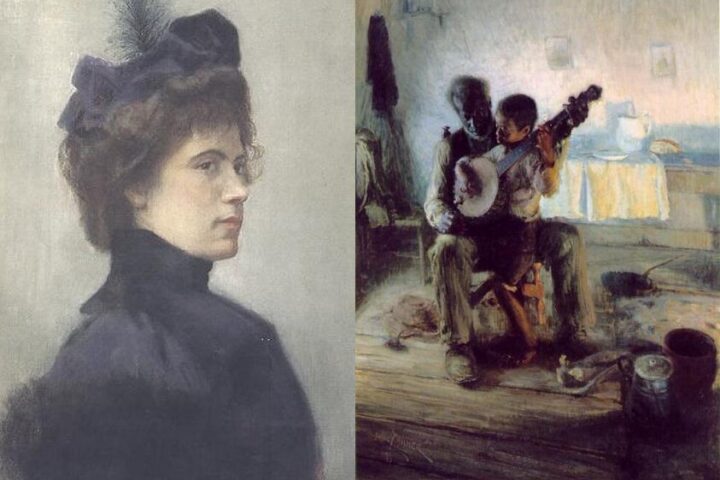

©Chris Ofili  ©Kara Walker

©Kara Walker