Contemporary African Art through a Different Lens

In the past decade, contemporary African art has moved from the margins to the global stage, with London’s 1:54 art fair playing a pivotal role in that shift. From the hyperreal portraits of Nigeria’s Ayogu Kingsley to the mystical, myth-infused visions of Brazil’s Gustavo Nazareno, and the deeply personal, multidisciplinary work of Moses Quiquine, artists from Africa and the diaspora are redefining what global contemporary art looks like. Once dismissed by critics like the late Brian Sewell, Black art now commands centre stage, with even institutions like Tate Modern celebrating its brilliance. This is a new era—bold, spiritual, unapologetically complex—and, above all, undeniable.

London’s 1:54

1:54 is one of the world’s leading celebrations of contemporary African art. Now held in three cities—New York, Marrakech, and its largest edition in London—it takes place at Somerset House during the city’s renowned Frieze art week. In just over a decade, London’s 1:54 has become a highlight of the capital’s cultural calendar.

The fair showcases the work of hundreds of African artists from across the continent. Its name, 1:54, symbolises the inclusion of at least one artist from each of Africa’s 54 countries. Founded in 2013 by Moroccan curator Touria El Glaoui, daughter of the artist Hassan El Glaoui, the fair was established to improve the visibility and representation of contemporary African art on the global stage.

1:54 also serves as a quiet but powerful rebuttal to traditionalist critics—such as the late Brian Sewell—who once dismissed the continent’s artistic output as inferior to that of Europe. Ironically, contemporary African and diasporic art is now among the most sought-after and collectible in the world, with artists commanding increasingly high prices at auction.

Given the scale of the exhibition, it’s nearly impossible to spotlight every artist featured. However, here are a few personal favourites worth noting.

Ibrahim Bamidele

Ibrahim Bamidele is a Nigerian artist whose work beautifully fuses photography and painting, intricately embellished with vibrant Ankara fabrics. His artistic expression is deeply rooted in everyday experiences, often placing contemporary African figures within compositions rich in religious symbolism. In Madonna in Thought, for example, Bamidele presents a striking portrait of a woman immersed in quiet reflection—an image that evokes both spiritual depth and personal introspection.

In Paraclete, Bamidele explores humanity’s innate need for connection. The painting features two women seated side by side, weaving a visual narrative that reflects the themes of unity, intimacy, and the enduring power of human bonds.

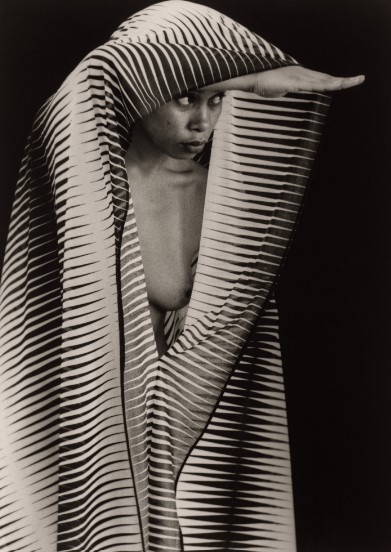

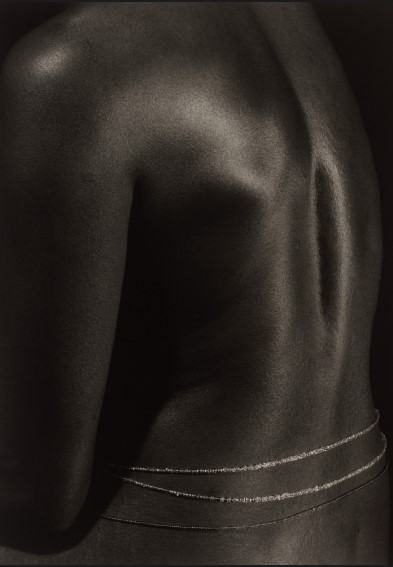

Angèle Etoundi Essamba

Angèle Etoundi Essamba is an artist whose work powerfully reflects on the identity of Black women. With roots in Cameroon, France, and the Netherlands, Essamba brings a rich, multicultural perspective to her practice. Her photography challenges the stereotypical portrayals of Black women often seen in Western media, offering instead a space where her subjects reclaim agency and assert control over their own narratives.

Ayogu Kingsley

Ayogu Kingsley is a Nigerian artist whose work centres on legendary African and African American historical figures. Through his hyperrealist portraits, he imagines powerful encounters and moments, often capturing these icons at the peak of their political or creative influence. His paintings have been described by The Guardian as so lifelike they feel almost tangible.

Kingsley’s work not only celebrates widely recognised figures but also brings attention to those whose legacies risk being forgotten. One such figure is Thomas Sankara, the revered Pan-Africanist and former president of Burkina Faso. During his brief but impactful tenure—he served just four years before his assassination in 1987—Sankara championed women’s rights, outlawed female genital mutilation, and promoted national self-sufficiency, rejecting dependence on loans from institutions like the IMF and World Bank.

Ayogu brings these historical figures vividly to life, lifting them from the pages of history and placing them directly before the viewer. His portraits create an uncanny sense of presence—looking at them, you feel as though you’ve met these icons face to face.

Gustavo Nazareno

Brazilian painter Gustavo Nazareno’s work stands in striking contrast to that of Kingsley. While Kingsley grounds his subjects in historical realism, Nazareno delves into the mystical, drawing inspiration from African religions, mythology, and spiritual traditions. A self-taught artist, he creates hybrid figures that transcend age and gender, inhabiting dreamlike landscapes that feel both otherworldly and deeply rooted in cultural memory. His bold use of light and shadow, along with the emotive intensity of his subjects, has led some critics to hail him as a contemporary Caravaggio.

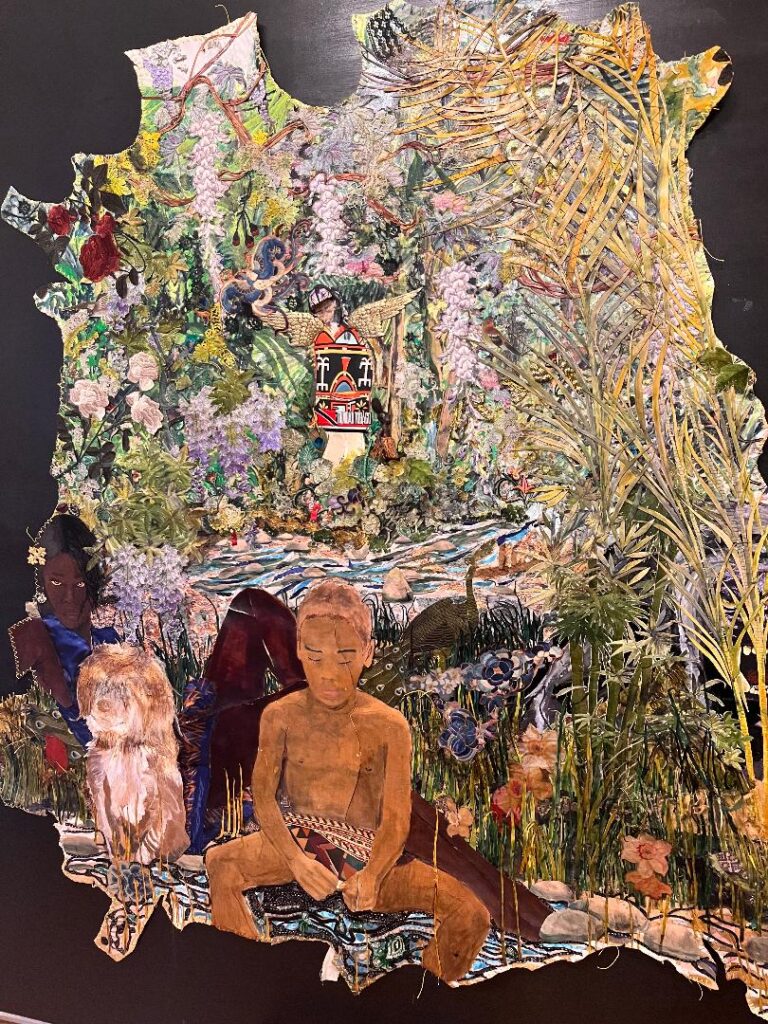

Moses Quiquine

Beyond 1:54, another contemporary Black artist from the African diaspora who is poised for a remarkable future is Moses Quiquine—a British artist with French Caribbean roots. A former artist-in-residence at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, Quiquine is a creative force whose work resists easy categorization. He seamlessly blends a range of disciplines, from painting and fashion design to sculptural practices that engage directly with the physicality of his materials.

Spirituality is a vital component of Quiquine’s work. A devoted practitioner of Nichiren Buddhism, he draws heavily from his personal journey of introspection and growth. As he often states in interviews, “It’s all about our personal growth, how far we come in ourselves. Some people never get there.”

Quiquine is also fiercely independent in his approach to the art world. With the increasing popularity of Black art, he stresses the importance of thoughtful representation. “For me, it’s really important that I feel a gallery truly understands who I am—and, of course, understands the work I create. If they don’t, then what’s the point? It can’t simply be about the money. Being an artist, you want to make sure you’re not just a commodity for the gallery.”

His work is already gaining recognition in major galleries, and it’s only a matter of time before it reaches museums and collections around the world. One particularly poignant piece, Garçon, exemplifies his artistic and emotional depth. The painting explores the difficult choices a young Black boy faces once he becomes aware of the societal projections placed upon him. Hovering above the child is an angelic guardian figure—made all the more powerful when you learn that it is a tribute to Quiquine’s cousin, a rising soccer star who tragically passed away in a freak accident earlier this year. The painting resonates with a deep spiritual connection that seems to transcend death.

With the success of exhibitions like 1:54 and the rise of young, independent Black artists such as Moses Quiquine, one can’t help but wonder what the late art critic Brian Sewell would make of this new era—an era in which Black art has rightfully claimed its place on the global stage. Even Tate Modern’s iconic Turbine Hall now features the monumental work of African master El Anatsui, a powerful symbol of how far things have come. Would Sewell be surprised? Almost certainly. But one hopes that, in the face of such undeniable talent, he would simply acknowledge the work for what it is: extraordinary.

- In the Black Fantastic

- The Art of Drawing

- African Fashion

- Palais de Lomé, Togo’s Guggenheim

- Painting: Silence & Correspondence