Pierre II, Duke of Brittany: A Reign of Diplomacy, Defiance, and Independence

(1450–1457)

When Pierre II became Duke of Brittany in 1450, he inherited more than a title—he stepped into a volatile political landscape shaped by French ambition, English aggression, and simmering dynastic tensions. Often overlooked or mischaracterized as a mere caretaker duke, Pierre proved instead to be one of the most politically astute and strategically cautious rulers in Brittany’s history. His short reign—just seven years—was marked by efforts to strengthen the duchy’s autonomy, modernize its institutions, and defend its sovereignty from both friends and foes.

A Defiant Start: Homage to the French Crown

As with previous dukes, the French monarchy—then ruled by the Valois dynasty—demanded that Pierre II perform liege homage, a binding oath of loyalty that would effectively make Brittany a vassal state. But Pierre, fiercely protective of Breton independence, refused. On 3rd November 1450, he offered only simple homage, consistent with traditional Breton custom.

The ceremony was anything but smooth. Pierre clashed with prominent French figures, including Dunois (the Bastard of Orléans) and Chancellor Juvénal des Ursins. He agreed to remove his cap and sword in deference, but firmly refused to kneel before the king. Eventually, King Charles VII and his advisors accepted this compromise.

Yet the incident sparked controversy. Some French observers claimed Pierre had in fact performed liege homage, insisting he had slightly bent a knee when receiving the king’s ceremonial kiss. Pierre shot back with a firm warning, urging the French crown not to infringe upon the ‘rights and privileges of the Duchy of Brittany.’

A Savvy Political Operator

France may have been riding high after its 1450 victory at Formigny in Normandy, but its hold on power remained shaky. The English still occupied Calais and Guyenne, and the threat of renewed conflict loomed large. The last thing the Valois wanted was a feud with Brittany. For his part, Pierre used the moment wisely, consolidating his position and charting a course of quiet resistance.

Far from the passive figure some chroniclers describe, Pierre was a politically astute and forward-thinking leader. He reformed the duchy’s institutions and convened the Estates of Brittany six times—more than any other duke—earning him a reputation as the most parliamentary ruler in Breton history.

Gradually, he distanced Brittany from French influence. He severed ties with pro-French factions in Nantes, denied the French king any royal prerogatives in Brittany following a formal inquiry, refused to appear before the Parliament of Paris when summoned, and began forging strategic ties with the rising kingdoms of Castile and Portugal.

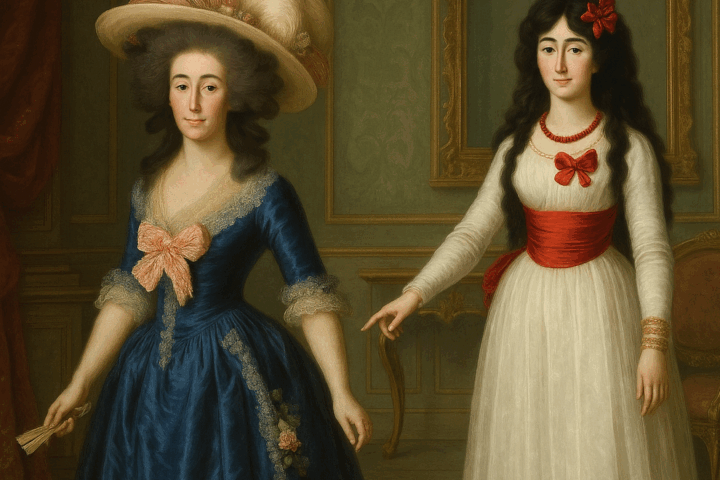

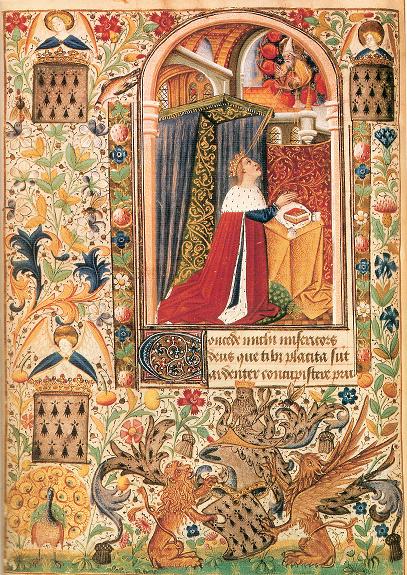

At home, Pierre elevated the prestige of his court, codifying etiquette and expanding the influence of the Order of the Ermine—a chivalric order originally founded by Duke John IV and known as the Epy under Pierre and his predecessor Francis I.

Succession Crisis: Scotland Enters the Fray

In 1453, Pierre found himself in the crosshairs of yet another royal dispute—this time with Scotland. King James II accused him of illegitimately seizing the Breton throne, claiming that Pierre had bypassed the inheritance rights of his two nieces, Marguerite and Marie of Brittany (6). He also charged Pierre with unlawfully detaining his sister, Isabeau of Scotland—the widowed duchess—and denying her access to her dowry.

James II, a shrewd and ambitious monarch, had broader plans. He intended to marry Isabeau into Scottish nobility and had political designs on Brittany itself. To defuse the crisis, Pierre called off plans to marry Isabeau into the House of Navarre and, more significantly, arranged a marriage between Marguerite of Brittany and François d’Estampes—second in line to the duchy after the aging Count Arthur of Richemont.

Still, the damage was done. Relations between Brittany and Scotland remained tense, exacerbated by the longstanding Franco-Scottish alliance. Pierre was particularly outraged by France’s diplomatic support of James II, seeing it as a threat to Breton sovereignty. Brittany, like England, now feared being caught between two powerful and increasingly hostile allies: the Valois and the Stuarts.

Piracy and the English Grievance

Even during peacetime, Brittany struggled to rein in its independent-minded seafarers. Attacks on English ships off the Breton coast were frequent. In times of war or political tension, piracy skyrocketed. Under Francis I, these maritime raids were used by the English as a pretext for the brutal sack of Fougères, a rich Breton town, not far from Maine and Normandy.

At the Louviers Conference in June 1449, English envoys representing Somerset estimated the damages from Breton piracy at over three million gold crowns, accusing Breton privateers of spreading terror along the English coast.

Although the sack of Fougères wasn’t directly caused by these raids, the fact they were cited in diplomatic talks shows how serious the issue had become.

The English, however, were no strangers to piracy themselves. They regularly targeted Breton merchant vessels. Historian Charles Kingsford, in Prejudice & Promise in 15th-Century England, documented numerous attacks by English corsairs in the 1440s. For small-scale Breton shipowners—most of whom owned just one vessel—the loss of a ship often meant financial ruin and starvation.

Toward the end of his reign, Pierre II formally complained to Charles VII about the growing number of safe-conduct passes issued by the Admiral of France to English ships. He warned of ‘great evils, looting, and damage […] inflicted upon the lands and subjects of Brittany.’

A Reign of Balance and Resolve

In his seven-year rule, Pierre II steered Brittany through turbulent waters with caution, vision, and diplomatic skill. He modernized institutions, defended Breton rights, and quietly distanced his duchy from overbearing French influence. While he never waged grand wars or expanded territories, his legacy was no less significant: Pierre II proved that a small but determined state could stand its ground in a world ruled by giants.

Glossary of Key Figures

Arthur, Count of Richemont (1393–1458)

Second son of Duke John IV of Brittany and Joan of Navarre (later Queen of England). He was appointed Constable of France by Charles VII and played a key military and political role in the later stages of the Hundred Years’ War.

Charles VII, King of France (1403–1461)

Son of Charles VI and Isabeau of Bavaria. Disinherited by the Treaty of Troyes in 1420 in favor of Henry V of England. Mocked as the ‘little king of Bourges,’ he regained the French crown after a long struggle, notably aided by Joan of Arc.

Francis I, Duke of Brittany (1414–1450)

Eldest son of Duke John V and Joan of France. Known for arresting his brother Gilles of Brittany, whose suspicious death haunted his reputation. He ended Anglo-Breton collaboration and was married to Isabeau of Scotland.

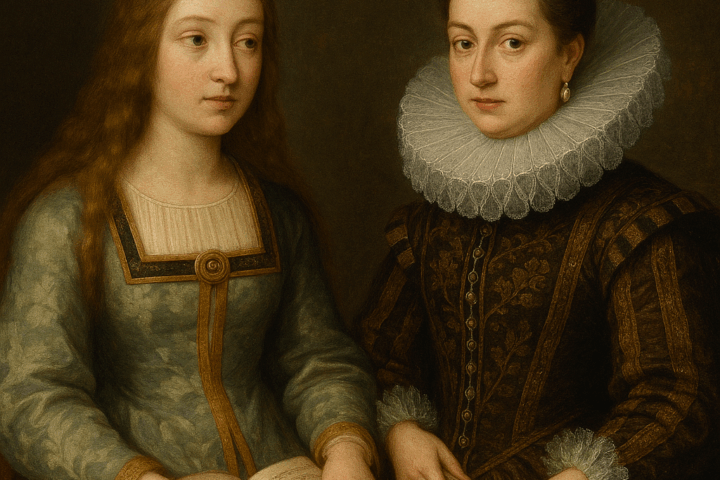

Isabeau of Scotland (c. 1425–1494)

Daughter of King James I of Scotland and Joan Beaufort. Originally intended to marry Duke John V, she instead wed his son, Francis I of Brittany. She bore two daughters: Marguerite and Marie. Her sister, Margaret of Scotland, married the future Louis XI of France.

James II, King of Scotland (1430–1460)

Ascended the throne at age of six after his father’s assassination. A popular monarch, he supported the Franco-Scottish alliance and sought to assert influence in Brittany by promoting claims through his sister Isabeau.

John IV, Duke of Brittany (1339–1399)

Son of John of Montfort and Joan of Flanders (known as ‘Jeanne la Flamme’). Anglophile in policy, he spent time in England and secured control of Brittany with English military aid. He initiated the enduring Anglo-Breton alliance.

John V, Duke of Brittany (1389–1442)

Son of John IV and Joan of Navarre. He pursued a policy of neutrality and friendly relations with England, helping to preserve Breton autonomy from France.

Edmund Beaufort, Duke of Somerset (1406–1455)

English noble and key commander during the Hundred Years’ War. Advisor to King Henry VI and close to Queen Margaret of Anjou. He sacked Fougères in Brittany, triggering the end of the Montfort-Lancaster alliance.

Richard of York (1411–1460)

Direct descendant of Edward III. His political and dynastic claims led to the Wars of the Roses. Named Lord Protector during Henry VI’s incapacity. Killed in battle; his son would become King Edward IV.

Sources

- Bertrand d’Argentré, Histoire de Bretagne, Paris, 1668, 3e éd. (1e éd. : 1588), 951.

- Du Fresne de Beaucourt, Histoire de Charles VII, IV, éd. 1881–1891, 313–314.

- Arthur de la Borderie, “Les ducs de Bretagne de la maison de Montfort (1364–1488),” Revue de Bretagne et de Vendée, juil–sept. 1866, 157–160; La Bretagne aux derniers siècles du Moyen Âge (1364–1491), Rennes, 1904, 166–167.

- Dom P.H. Morice, Mémoires pour servir de preuves à l’histoire ecclésiastique et civile de Bretagne, II, 1557–1668. Also in Émile Lefort des Ylouses, “Le sceau et le pouvoir,” S.H.A.B., 68 (1991), 137.

- Michael Jones, “Les signes du pouvoir : l’Ordre de l’Hermine…”, S.H.A.B., 68 (1991), 141–158.

- The Daughters of Francis I and Isabeau of Scotland.

- Du Fresne de Beaucourt, VI, 132–135; Exchequer Rolls of Scotland, G. Burnett, éd. 1882–1883, vol. V–VI; MacDougall, 43–44; Morice, II, 1617–1645.

- Morice, II, 1675–1682.

- A. Johnson, Duke Richard of York, 1411–1460, Oxford, Clarendon, 40.

- Négociations du 24 au 29 juin 1449.

- Joseph Stevenson (éd.), Narratives of the English Expulsion from Normandy, Rolls Series, 1863, 418; Morice, II, 1474–1475.

- [14] Kingsford, Prejudice & Promise in XVth Century England, 91–94.

- [15] J.P. Leguay & H. Martin, Fastes et Malheurs de la Bretagne ducale, Rennes, 1982, 208.

- [16] Morice, II, 1693–1695.