Gilles of Brittany, the anglophile prince who was murdered

Gilles of Brittany

(1420-1450)

Auteur: Pierre Scordia

The murder of Gilles of Brittany had repercussions throughout the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. It dramatically changed the course of Anglo-Breton relations and moreover led to serious consequences for the Anglo-French political landscape.

Gilles of Brittany was the third son of John V, Duke of Brittany, his favourite son if we are to believe the chronicles. As a child he spent two years at the court of Henry VI and became a close friend of the king, receiving an annual allowance of 250 marks. According to the Breton chronicler Bourdeaut, Gilles was also host to the Earl of Warwick, the king maker during the English Wars of the Roses. By sending his son to England, John V was showing respect for Monfort tradition: an important member of the ducal family must reside for some years across the Channel. It is said that Gilles was seduced by the English court and that he even possessed traits of character typically English: ambitious, haughty, violent, cultivated, with a taste for luxury. For Gilles, wealth represented honour; he embraced the chivalrous mind-set of fifteenth and sixteenth century Western civilisation. For their part, the English nobles were full of praise for the excellent manners of this Breton prince.

If Gilles’ Anglophilia did not theoretically cause him problems at the Breton court in Nantes, certainly his ambitions greatly annoyed his eldest brother. As soon as his father died, Gilles complained of his bad luck to his brother Francis, the new duke, an especially benevolent prince when it came to French interests. Gilles was reluctant to take a public oath of obedience to Charles VII of Valois. Gilles did not support the Valois claim to the French Crown and he was reluctant to pay homage for his new lands of Chantocé and Ingrandes in Anjou bequeathed to him by his late father, land which had been confiscated from the notorious Gilles de Rais. Thus one may question the sincerity of John V’s fondness for his third son for if Gilles had truly been his favourite child, why should the old duke have left to him in his will French lordships which had once belonged to the terrible serial killer Gilles de Rais? Would he not have preferred to bequeath to him a rich Breton lordship in order to spare his Anglophile son from taking an oath of allegiance to the King of France? Gilles begged in vain to be granted instead a Breton appanage in order to spare him such an abhorrent duty.

At the beginning of his reign, Francis I, anxious to preserve Breton neutrality in the Anglo-French conflict, made use of his younger brother. He sent Gilles to Henry VI’s court on a diplomatic mission to plead with the king the restitution of the Richemont county in England. But, rather than defend his elder brother’s interests, Gilles chose instead to devote his time to his own business and solicited Henry VI to help him obtain a rich Breton appanage. Henry VI not only defended him but granted his Breton friend an annual allowance of 2,000 nobles (gold coins). Gilles, satisfied with this support, swore allegiance to him.

This act of defiance unsurprisingly angered Charles VII, who took the decision to confiscate the French territories belonging to Gilles: Chantocé and Ingrandes. These reprisals put Francis I into an embarrassing position and pushed him to eventually opt for the lesser of two evils by negotiating with the French king rather than grant the Breton fiefdom requested by his brother. He managed to secure the return of the Chantocé domain to his family but was obliged to relinquish Monfort rights to the barony of Rays.

However, the situation became far more complicated when the Duke of Somerset, who wanted to put pressure on Duke Francis I to grant Gilles a Breton appanage, ordered his troops to plunder La Guerche, a Breton town right on the border with France, in December 1443. This was a counterproductive initiative which infuriated the Duke of Brittany, who at once recalled his brother from England. Back on the continent, overconfident of his strength given the promised diplomatic and military support of the House of Lancaster, Gilles began to threaten his elder brother. He set off for Guyenne and Normandy (English France) in order to enlist the help of the English to hatch a plot.

On July 26th, 1445, Francis I intercepted a letter in which Gilles informed Henry VI that if his brother refused to cooperate, he would be prepared to deliver to the English the Breton land belonging to his wife, the wealthy Françoise of Dinan whom he had kidnapped and married in 1444. This eight-year-old girl was the richest heiress in the duchy and one of the most coveted women. By this coup de force, Gilles had become one of the most powerful lords in Brittany. By this time he controlled two major fortified places where he had been appointed governor by his brother: the towns of Saint-Malo and Moncontour as well as – thanks to his wife - the lordships of Châteaubriant, La Hardouinaie, Montafilant and Le Guildo. By this marriage, Gilles had made himself many enemies, notably Arthur de Montauban and the Earl of Laval, both of whom also laid claim to the hand of the rich heiress. Francis I had to pay 20,000 crowns to Guy XIV of Laval in compensation and moreover was also obliged to grant 6,000 crowns to the Rohan family, a very powerful house in the duchy.

Let us remind ourselves that in the political context of fifteenth century Brittany, Gilles had as much right to be a pensionary of the King of England as his uncle, the Duke of Richemont, to be one of the King of France. What worried the Duke of Brittany, a man attached to his quasi-royal prerogatives, was the threat of a foreign invasion, whether it be French or English. Now, faced with the growing hostility of his brother, Francis I began to fear a Lancastrian intrusion into his duchy. However, under the influence of his uncle Arthur who feared above all a fratricidal struggle in the Montfort house, he forgave his brother's betrayal on October 19th, 1445. In return for this pardon, Gilles was to renounce his command of Saint-Malo and Moncontour.

The English made a strategic error by failing to recognise the growing isolation of Gilles at the court of Nantes and the strategic losses incurred by the disappearance of a pro-English administration in the ports of Saint-Malo and Moncontour. On the contrary, they put all their weight behind Gilles. On October 25th, 1445 Henry VI called for Francis I to grant Gilles a Breton appanage, to respect the alliance between his late father John V and England and then went on to remind Francis of the family ties uniting the Montfort and the Lancaster. To make matters worse, the Lancasters had further entrenched Gilles in his intransigence by promising him the rich English County of Richemont.

Certain more cautious English captains, such as Thomas Hoo, Robert Roos, and Guillaume Roskill, advised Gilles and his wife to leave Brittany while there was still time. Despite these fears for his safety, Gilles did not move. He remained in his castle of Le Guildo, and even pushed his luck further by recklessly mentioning to his brother’s envoy, Jean Hingant, that the duke was his mortal enemy and that he was prepared to go to England to seek aid in order to wage war on him. Moreover, rumours began to spread in the European Courts where it was alleged without any proof that Gilles had received the order of the Garter and accepted the title of Lord High Constable of England.

Faced with the danger of an English invasion, Francis I had no other choice but to neutralize his brother and freeze all diplomatic relations with Henry VI who was conspiring against his interests. He accused Gilles of high treason and asked the King of France to send troops from Mont-Saint-Michel to arrest him. By this stratagem, he hoped to avoid being accused of having orchestrated his brother’s arrest for reasons of personal vengeance.

During his detention, Arthur de Montauban, who jealously coveted the hand of Françoise of Dinan and was in the pay of the Duke and Charles VII, murdered Gilles. The incarceration and assassination of Gilles of Brittany was perceived as a fratricidal act throughout Europe and especially over the English Channel dealing a fatal blow to the old benevolent neutrality of Brittany towards England and worse still, triggering the resumption of Anglo-French war. The failure of the Anglo-Breton alliance rang the death knell of Lancastrian Normandy and the English presence on the Continent.

FΩRMIdea Nantes | Brittany - 10th March 2018. Lire en français

Glossary | Gilles of Brittany

Arthur de Montauban: (died in 1478) A great Breton nobleman, supporter of the alliance with France. His father was chancellor to the Queen of France, Isabella of Bavaria, wife of Charles VI. He coveted the hand of Françoise de Dinan who in the end married Gilles de Bretagne. Arthur de Montauban was the instigator of the ill-treatment and then murder of Gilles of Brittany, brother of Duke Francis I. When the new Duke Peter II of Brittany wanted to prosecute the perpetrators of Gilles’ murder, Arthur de Montauban took refuge in the French court and became one of the favorites of Louis XI.

Charles VII, King of France: (1403 - 1461) Son of Charles VI and Isabella of Bavaria, he lost his rightful claim to the French crown in 1420 in favor of Henry V of England and his descendants. Mocked and insulted, known as the “Little King of Bourges", he recovered the French crown after a very long fight. He made use of Joan of Arc to establish his legitimacy.

Francis I, Duke of Brittany: (1414 - 1450): Eldest son of John V and Joan of France. He was responsible for the arrest of his brother Gilles of Brittany. The murder of the latter, during his incarceration, haunted him thereafter and tarnished his international image. He put an end to the policy of collaboration between Brittany and England. He was married to Isabella of Scotland, daughter of King James IV.

Françoise de Dinan: (1436 - 1499): Daughter of Jacques de Dinan and Catherine de Rohan. She was considered the richest heiress in Brittany. She was sequestered at the age of 8 and forcibly married to Gilles of Brittany. When her husband was arrested, she was thrown into a dungeon. Once released, she was married to Guy XIV of Laval. Later she became the governess of the well known Anne of Brittany.

Gilles of Brittany: (1420 - 1450) Unfortunate son of John V and Joan of France. Partisan of the alliance with England and friend of King Henry VI, he was imprisoned for high treason under the orders of his brother, Francis I and then murdered by Arthur de Montauban.

Gilles de Rais: (1405 - 1440) Lord of Brittany and Anjou, he fought the English from within the French troops, notably alongside Joan of Arc. Back in his homeland, he performed black masses, paedophile acts and human sacrifices. To this day he remains one of the biggest serial killers in French history. He was protected for a long time by Duke John V of Brittany in spite of the suspicions surrounding him. But by dint of his violation of ecclesiastical immunities, he was arrested and tried on the Duke's orders. He was sentenced to death for his numerous crimes in Nantes and his lands confiscated by the ducal crown.

Henry VI, King of England and King of France: (1421 - 1471) Son of King Henry V and Catherine of Valois. Crowned Sacred King of England at Westminster Abbey and King of France at the Cathedral of Paris – a city held by the Burgundians. His claim to the French crown was challenged by the “Dauphin”, Charles VII of Valois. Like his maternal grandfather, he experienced episodes of madness, which forced his wife, Margaret of Anjou, to govern on his behalf. Her regency was soon challenged by Richard of York, which led to the beginning of the Wars of the Roses.

Joan of France, Duchess of Brittany: (1391 - 1433) Daughter of Charles VI and Isabella of Bavaria, wife of John V. Mother of Francis I, Pierre II and Gilles of Brittany. She stood firm when her husband was held prisoner in 1420 by the Penthièvre, allied to the French, who challenged the Montfort claim to the Breton duchy. Joan gave them nothing and continued the pro-English policy of her husband.

Robert Roos: Contemporary of Regent Bedford and Henry VI. Roos was appointed English Ambassador during the Treaty of Tours in 1444, a treaty in which were concluded a truce with France and a royal marriage between Henry VI and Margaret of Anjou.

Somerset, Edmund Beaufort, Duke of Somerset: (1406 - 1455) Son of Margaret Holland and Count John of Somerset, half-brother of Henry V. He was also the nephew of the Archbishop of Winchester. He was one of the main military leaders of the English army during the Hundred Years War. He became advisor to King Henry VI and was a favourite of the Queen of England, Margaret of Anjou. He was the main instigator of the plunder of Fougères, a rich Breton town, the disastrous consequence of which was the immediate end of the old alliance between the Montfort and the Lancaster, a prelude to the fall of English France. Before obtaining the title of Duke, he was known as Count and Marquis of Dorset.

Warwick, Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick: (1428 - 1471) Nicknamed the “Kingmaker”. A very powerful nobleman who first supported Henry VI but, when their relationship deteriorated, changed sides during the Wars of the Roses. Together with Richard of York, he actively participated in overthrowing Henry VI and replacing him with Edward IV, son of the Duke of York. He helped Henry IV and Margaret of Anjou to regain the throne of England in 1470. It proved to be a short-lived victory since he was defeated and killed at the Battle of Barnet in 1471.

Other articles by the same author:

1. England & John IV Duke of Brittany

2. Joan of Navarre, Duchess of Brittany and Queen of England (from 1386 to 1437)

3. Gilles of Brittany, the anglophile prince who was murdered

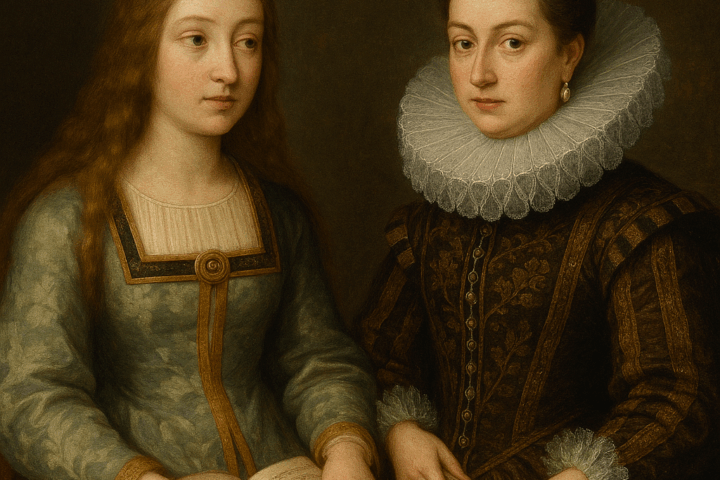

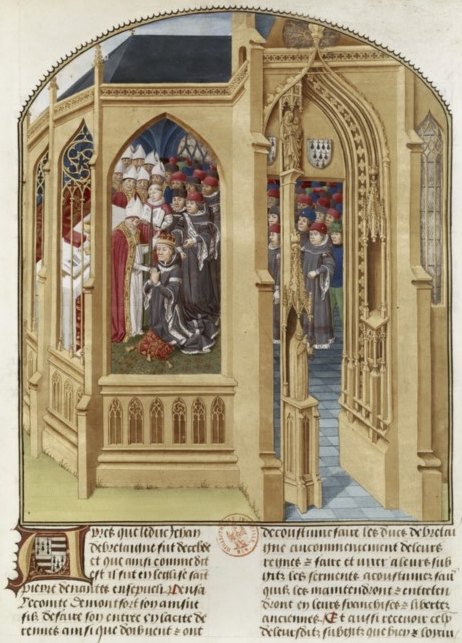

Francis I's coronation in Rennes, Brittany. Gilles attended the ceremony.

Francis I's coronation in Rennes, Brittany. Gilles attended the ceremony.