the extraordinary life of Elisabeth Tschumi

From a Swiss farm to a palace in Constantinople

Author: Rinaldo Tomaselli

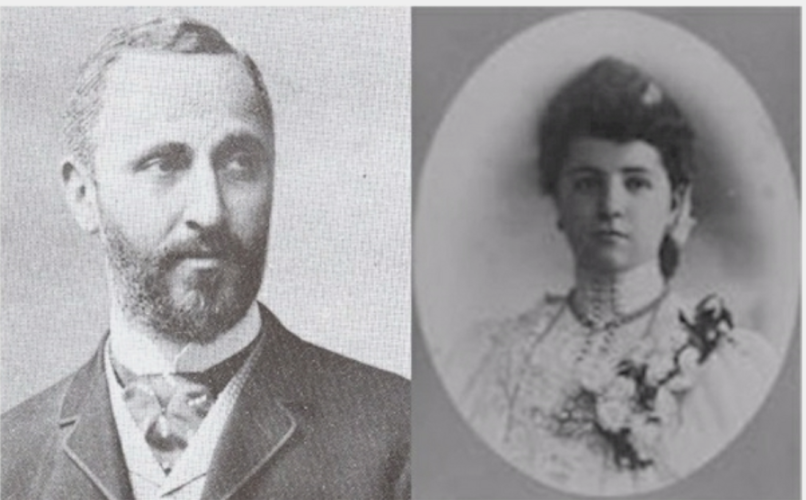

The extraordinary life of Elisabeth Tschumi who was born and brought up in a Swiss peasant family and then became the wife of the last vizier of the Ottoman Empire.

Elisabeth Tschumi: Born on June 24th, 1859 in Wolfisberg, Upper Aargau, Swiss Confederation. Died Lady Afife Okday on February 17th, 1949 in Istanbul, Turkish Republic.

Switzerland

Upper Aargau is a Swiss plateau which remained part of the canton of Bern when the canton of Aargau gained its independence from the Helvetic Republic in 1803 and became a Swiss canton in its own right; the territory extends mainly to the south of the river Aar, which passes through Aargau and then flows into the Rhine. North of the river, at that time, there were Protestant settlements almost completely surrounded by Solothurn Catholic communities, all formally part of the Bernese region. These were located on the flank of the Jura Mountains and separated from the French-speaking Bernese Jura only by the Balsthal Valley. Thus, historically, culturally and economically these few villages remained linked to the south of the Bern canton. Wolfisberg is one of these villages, situated approximately 700 metres above sea level, overlooking the Aare Valley, like a belvedere with different views, from the peaks of the Tyrol and Mont Blanc, through the Eiger, the Mönch and the Jungfrau.

This was the bucolic setting into which Elisabeth Tschumi was born on June 24th, 1859. Her father Jacob was a farmer and forest ranger. The family, in common with most of the inhabitants of this small village, was of modest means, owning a few cows. A good number of the village men found work at the Von Roll factory in Klus-Balsthal, a foundry a few kilometres away from Wolfisberg. The women and children took care of the family farm and foraged for wild berries and mushrooms to supplement meals.

Elisabeth Tschumi, like the other children of the village, understood from an early age that life meant work; leisure and daydreams having no place in the harsh living conditions of Bernese peasants in the second half of the 19th century. And when she went out walking, as she liked to do, she never failed to bring home food she had gathered along the way: raspberries, wild strawberries, mushrooms or medicinal plants, all abundant in the forests of the Jura. She sometimes walked further afield, to the other side of the mountain, near the "Welschs’ Pipe", which more or less marked the boundary between the German-speaking and the Swiss-French who were called, rather pejoratively, "the Welschs".

Until her adolescence, Elisabeth Tschumi had little opportunity to travel except to occasionally visit Solothurn and from time to time Berthoud or Bern. She dreamed of seeing a big city one day, maybe Basel or Paris. It so happened that a friend of the Tschumi family who lived in Bern, rubbed shoulders at work with the staff of several embassies. One day, he was asked if he happened to know of an honest and hardworking girl to care for the children of the British ambassador to Athens. He thought of Elisabeth who was delighted to accept the job. At last, her dreams of seeing a big city were to come true; she was going to be a governess in Athens!

Greece

Thus, at the age of 17, Elisabeth Tschumi packed her suitcase and set off on the long journey to Athens. After a trip of several days across the Balkans she arrived at the station of the Hellenic capital, where a gentleman she found "very chic" was waiting to welcome her. She assumed he must be her employer, but in fact, he was the ambassador's chauffeur! The British Embassy was an impressive two-storey neoclassical house; white marble steps led to a small garden with the house entrance under a colonnade. Elisabeth was greeted by the ambassador’s wife, who was accompanied by her daughters. She was expected to care for the children and supervise their education, including teaching them French. She was given a room to herself and at mealtimes and social occasions sat at the family table. A completely new life had begun for this young peasant girl from Wolfisberg.

Nearly three years had passed and Elisabeth Tschumi had become a pleasant and confident woman. Educating children, good manners and etiquette held no more secrets for her. She had learned Greek to communicate with the domestic servants but spoke exclusively in French with her employers and their children. One day, a soirée was announced at the British Embassy; a dinner was to be given in honour of the Ottoman diplomatic representatives in Athens. Elisabeth Tschumi was to attend, as usual. The young Swissess found herself blushing under the admiring gaze of the young and handsome chargé d'affaires, Ahmet Tevfik Bey. Towards the end of the evening, Elisabeth asked permission to ensure everything was fine in the children's rooms, before herself retiring to bed. The chargé d'affaires discreetly slipped her a message inviting her to meet him the next day at 4pm at the Palace Hotel café, on Stadiou Street.

Ahmet Tevfik Bey was born on February 11th, 1843 in Constantinople, capital of the Ottoman Empire. His family was from Crimea and his father was a pasha and cavalry general, stationed in the Danube region. After his mother had died, shortly after his birth, his aunt had taken care of his education, ensuring he became fluent in Persian, Arabic and French. He completed his military service and rose to the rank of officer, but at the age of 22 left the army to enter the Foreign Office. In less than ten years, he had risen through the ranks, being successively appointed chargé d'affaires in Rome then Vienna, St. Petersburg and Athens.

The next afternoon, Elisabeth made her way to the Palace Hotel. She was barely 20 years old; her date was 36. It was the start of an idyllic time of courtship. They were from two different worlds, but found they had much in common. She found herself both attracted to and frightened by Ahmet Tevfik’s world. For her, the Ottoman Empire, though powerful, was a backward state ruled by a cruel Sultan who, in the corner of his palace kept a harem filled with captive women guarded by terrible black eunuchs, who wouldn’t hesitate to behead anyone daring to enter or leave this gilded prison. When the Sultan tired of one of these wretches, he had her put in a sack and thrown alive into the Bosphorus. These old clichés and prejudices made Ahmet Tevfik laugh. He spent hours describing Constantinople to Elisabeth, the life of its people and the wonders of the Bosphorus’s metropolis.

Months passed, walks and outings followed one after another and then came the day when Ahmet Tevfik asked Elisabeth Tschumi for her hand. She happily accepted the marriage proposal, however, aware of Muslim traditions, made him promise that she would remain his one and only wife. Ahmet Tevfik agreed, but he too had a request: to conform to the expectations of society, Elisabeth should convert to Islam. Now Elisabeth was not especially pious, but she was from a practising Protestant family, and was unwilling to give up her religion of birth. Ahmet Tevfik did not insist, but suggested that he could call her by a Muslim name, which she agreed to.

Marriage in Athens

The marriage took place at the Ottoman Embassy in Athens at the end of 1879 and Elisabeth became Afife. Sadly their first child did not survive. In October 1881 a second child was born, Ismail Hakki and then in March 1883, a third boy, little Ali Nuri. When their second son was two years old, Elisabeth asked her husband when he planned to have the children baptised. Ahmet Tevfik was at first surprised, then burst out laughing and explained that Muslims were not baptised, but circumcision was expected around the age of six or eight. Elisabeth, who spoke French with her husband, would switch to Greek or Swiss German when she was angry. She began to protest in these unknown languages to Ahmet Tevfik. The storm between them passed but Elisabeth, whilst accepting that her children would grow up as devout Muslims, felt strongly about this connection to her roots.

She went quietly to visit the pastor of the German community in Athens, but he refused to baptise the children without the father’s consent. Finally, she found a way around the problem with the help of Victoria, the Greek governess, who introduced her to an Orthodox priest who agreed to baptise the children for 25 pounds of gold. He refused however to do so using their Muslim names and so for the occasion, Ismail became Isidore and Ali, Alexander. One year after the children were baptised (1885), the family moved to Berlin, where Ahmet Tevfik had been appointed ambassador.

Berlin

Elisabeth did not enjoy the frivolous way of life of the German capital and struggled to play her role as ambassador's wife, but since it was customary for Muslims not to show their wives in public, she managed to avoid receptions and social events. She devoted herself to her children, especially her two little girls Zehra and Naile, new additions to the family.

All this time, Elisabeth had kept in touch with her own family. She had never once returned to her village in Upper Aargau, but she wrote frequently to her parents. Sometimes, amid the hustle and bustle of the German capital, she thought of the calm of the village, the wooded slopes of the Jura, the Alpine landscapes, the stunning view from the Weissenstein, a peak near Wolfisberg. In 1889 she decided to return for a visit with her two sons, a valet and the housekeeper. She was welcomed back to her village like a princess; the whole parish was there, including the municipal band, while schoolchildren from the village sang songs to welcome her. The inhabitants of neighbouring communities came out of curiosity and she was applauded as she stepped out of the car in the village square. In Wolfisberg, everything was the same as when she’d left, thirteen years before. The living conditions of the peasants had hardly changed and the simplicity of the family farm made Elisabeth feel ashamed in front of her children and even the governess. Her stay, which had been planned to last a week, was shortened to just three days.

Constantinople | Ottoman Empire

In 1895 Ahmet Tevfik was recalled to Constantinople. Sultan Abdulhamid II had appointed him Minister of Foreign Affairs. The family moved to the Ayazpaşa Palace on the edge of the Levantine district of Pera. The residence had 60 rooms, a large garden and overlooked the Bosphorus. It was here, in 1898, that the third daughter of the family, Gülşinaz was born. Ahmet Tevfik was successful in his role as minister and in 1897, after the Ottomans’ victory in the war against Greece, he received the title of Pasha.

The political events in the empire, the dismissal of Sultan Abdulhamid II and then the First World War, were to disrupt their lives. Ahmet Tevfik was appointed Grand Vizier (equivalent of Prime Minister) in 1909 under the reign of Sultan Mehmet Reşat V, but the Young Turks government, which took power, effectively dismissed him by appointing him ambassador to London in the same year.

England and France declared war on the Ottoman Empire in August 1914. Ahmet Tevfik and his family returned to Istanbul, but part of their palace had burned down in 1911 and the family lacked the funds for reconstruction. Elisabeth suggested renting out rooms in the palace wing which had not been touched by the fire, thus bringing in funds to rebuild the damaged wing. Ahmet Tevfik initially disapproved of this idea, given his social rank, but eventually agreed to it.

At the end of the war, the Ottoman Empire found itself in the losers' camp. Constantinople was occupied by the English, the French, and the Italians. German and Austrian nationals were expelled, the government fled abroad and the economic situation was catastrophic. It was in this context that Ahmet Tevfik was appointed Grand Vizier for the second time from November 1918 until 1919.

In 1920, the fate of the Ottoman Empire was not yet settled. Ahmet Tevfik took part in the Paris Peace Conference and refused to accept the terms of the treaty. He was appointed Grand Vizier a third time, while the Republicans led by Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk) occupied a large part of Anatolia and fought against the Greek army, which had taken advantage of the occupation by the Allied powers to advance to the heart of the country. In 1921, Ahmet Tevfik headed the Ottoman delegation to the London Conference, but another Turkish delegation also took part: the Republicans. Confronted by the moral strength of the Republicans, Ahmet Tevfik eventually conceded that the latter represented the legitimate government of Turkey and withdrew from negotiations.

On November 1st, 1922, the sultanate regime was abolished and on November 4th, Ahmet Tevfik Pasha resigned, while Sultan Mehmet VI left Istanbul on November 17th, 1922. On November 22nd, the Lausanne Conference was organised in order to agree conditions of peace and draw borders for the new Turkish Republic, which would be officially proclaimed on October 24th, 1923 in Ankara, the new capital. Thus, Ahmet Tevfik Pasha turned out to be the last grand vizier of the Ottoman Empire.

Istanbul | Turkey

Meanwhile, Elisabeth had transformed her house into a real palace. Prestigious guests visited or stayed, such as King Edward VIII of England and even Atatürk. The first years of the Republic were difficult for all Turks including Ahmet Tevfik's family, who no longer held any state office. The family palace was transformed into a hotel and became their only source of income. It turned out that Elisabeth had a good head for business and she did not shy away from hard work. She ran the hotel and created a vegetable garden, ensuring that both service and products were perfect, as she had been used to from her childhood in Upper Aargau.

The couple had no choice but to adapt to the reforms of the new Republic. In 1930, Constantinople officially became Istanbul. In 1934 surnames became compulsory. Ahmet Tevfik and Afife took the name of Okday. Ahmet Tevfik died on October 8th, 1936 at the age of 94. Elisabeth Afife passed away 13 years later, on February 17th, 1949 in the summer house of her son, Ali Nuri Alexander. According to her wishes and despite her Protestant religion, she rests in the family vault at the Adrianople Gate (Edirnekapı), alongside her husband. The palace hotel ran until 1979 until it became insalubrious and had to be closed. It was bought by a consortium and was unfortunately destroyed to make way for a skyscraper that has never risen. Sadly, the Park Hotel has disappeared for ever from the Istanbul landscape.

form-idea.com London, 7th November 2020.

Translated from French by Pierre Scordia, adapted and edited by Annie Clein.

Treacherous race traitor. May she be forgotten and her line ended